[

{

"name": "500x250 Ad",

"insertPoint": "5",

"component": "15667920",

"parentWrapperClass": "",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

Greta Anderson came home from church that summer Sunday afternoon, relaxed with a cup of tea in her favorite chair, and talked to a co-worker on the phone. The TV was on, she says, but she wasn't paying much attention to it until she looked over and saw her son's face on the screen.

She dropped the phone.

"I'll never forget that moment," she says. "That's how I found out that my son had done something that would send him to prison."

Her friend on the other end of the phone was at her door within minutes to see what was wrong. All Anderson remembers about the rest of that day, she says, is the steady stream of friends and family members stopping by to console her.

"The whole world changed in front of me and it's never been the same since," she says. "I prayed for God's help. I believe in the power of prayer. He's the only reason I'm here."

Anderson is part of a group of women in the Wesley's Mothers peer support program who meet weekly at Spiritus Christi Church at 121 North Fitzhugh Street in the City of Rochester.

The group, founded in 2007, is comprised only of women; the number fluctuates from five or six to about 20. They sit around a coffee table, where someone has usually put a plate of cookies and a box of tissues.

The women vary in age, race, and income, but they all have at least one emotionally-charged, life-altering experience in common: They are mothers of mostly sons who are or have been incarcerated in a county, state, or federal correctional facility.

Some of their children were still in their teens when they had their first encounter with the criminal justice system. Their crimes range from low level, nonviolent drug-related offenses to serious transgressions with long sentences: fraud, armed robbery, and sexual assault.

These women are not the faces of crime generally seen by the general public, whose attention typically goes to the victim and the victim's family.

When a son or daughter is convicted and sent to prison, that family is affected, too. And the mothers pay a particularly steep price. The women speak of deteriorated health due to stress, job losses from the constant distractions, financial problems, and clashes with family members.

One mother, Roberta Kelly, says that she developed severe arthritis and joint problems from the chronic tension. She was diagnosed with fibromyalgia and depression.

"All that hurt was eating me up inside," she says. "It's still eating me up alive. I've tried everything. I've gone to therapy and I was going to church a lot, too. Sometimes I would go four and five times a week."

The meetings with the Wesley's mothers have given her the only relief she's found after nearly 15 years of coping with her son's problems, Kelly says.

The worst part of having a child incarcerated, the mothers say, is the deep sense of personal loss and isolation. Family members and even close friends pull away, they say, and husbands and boyfriends often become disheartened from the pressures and leave.

And it becomes difficult, the women say, to hear other people share what's happening in their lives. Even ordinary stories involving a son or daughter's success: a promotion, the birth of a grandchild, a new house, can be painful to listen to, they say, so sometimes they avoid those people.

"In our own way, we're victims, too," says Jenny Leavy, a longtime member of the Wesley's Mothers. "You walk around and you have this shame that's with you all the time. It's as if you have a scarlet 'A' or some kind of a tattoo on your forehead, because the first thing people think is, 'It must be the parents' fault because it's always the parents' fault. So, what did you do?'"

CITY sat in on several Wesley's Mothers' sessions over the course of nearly a year. The names of the women in this story have been changed, and CITY agreed not to reveal the nature of their children's crimes, because the women fear for their children's safety in prison. And they're concerned that publicity might make their children' re-entry into home life more difficult.

No judgment

Each meeting of Wesley's Mothers begins with the rules of engagement: no criticism is allowed, what's said in the sparsely furnished room at Spiritus Christi stays in the room, and crime details are not usually discussed.

Each mother then shares her name and a word that describes how she's feeling that day: "anxious," "sad," "hopeful," and "grateful."

As support groups go, Wesley's Mothers is kind of a secret society. Support groups for mothers who have incarcerated sons and daughters are less common and a relatively new thing; though an exact number is hard to come by, many of the groups and online chatrooms around the country formed during the last decade.

Zero-tolerance policing has contributed to the need for these kinds of groups.

"A lot of us will say that our kids are good kids, but they made some bad decisions," says Karen Cook, a leader of Wesley's Mothers. "They're not monsters, and we're here because we still have hope and faith in them, and we sincerely believe they will turn their lives around."

The mothers don't dismiss the importance of fathers, but some have had bad relationships with men. Some left their husband or the father of the incarcerated child due to violence and abuse. Sometimes there were sharp disagreements over how to raise and discipline a child with emotional or developmental issues, or where to turn for help.

Society tends to see mothers as nurturers, and motherhood is intrinsically linked to womanhood in our culture, says Kaitlin Nicole Kall in a 2009 dissertation for Wesleyan University. Unconditional love and always being there for a son or daughter, including those who have committed serious crimes, is tantamount to being a good mother, she says, and a good woman.

The mothers can also play a pivotal role when grandchildren are involved, says Adele Fine, bureau chief of the family court division of the Monroe County Public Defender's Office. Frequently, grandmothers are the linchpins between incarcerated parents and their children, she says.

"I need them because if my client is going to have contact with his kids, it's most likely going to be through extended family like the grandmother," she says.

It's a huge responsibility that some of the mothers in the Wesley's group know all too well.

But the mothers often share something even more trying. Mothers are frequently seen as the biggest influence on early childhood and development, and a theory emblazoned on Western consciousness by Sigmund Freud is that mothers often bear at least some responsibility for their children's actions.

"Mother blame," Kaitlin Nicole Kall calls it.

And in some instances, the Wesley's mothers acknowledge that their personal problems did have unintended consequences. Angela Adams came to a group meeting shortly after her son was arrested. Adams has been in recovery for 11 years, and she's wracked with guilt about her son's future in prison. She attributes at least some of his defiant behavior and bad choices to her own.

"I was an active addict and his father was an active addict," she says. "He was exposed to a lot of the wrong things in life."

Adams says she wishes she knew earlier in her life what she knows now. Her son, her "baby boy," was speedballing — mixing heroin and cocaine — in the events leading up to his arrest.

"I was lucky enough to hear from God, as crazy as that sounds," Adams says. "I turned my life around 11 years and six months ago. But you never escape your past, and your mistakes get passed down to those you love. He was dealt a bad hand right from the beginning."

Life is different for her younger son, Adams says. He graduated from high school early and is headed to college.

"He had different parents, even though technically they were the same, but my husband and I were different people by then," she says. "We didn't expose him to all of that stuff that my older son was exposed to."

Adams says that her worst fear is that her younger son will get into trouble because she's had to devote so much attention to his brother's problems. She fears she's neglecting him.

"I pray every day, 'Please God, let my youngest son know that I love him and I am so very proud of him,'" she says. "'Please God, watch over him for me.'"

Some of the mothers say that their problems with domestic abuse and their disputes with family members spilled over onto their children's lives, leaving permanent scars.

Greta Anderson says that she left her husband to get away from an abusive situation, but that she might have made the break too late.

"My son had a really, really rough life," she says. "He came up with lots of abuse in our household. And he took the abuse for the three girls and me."

Signs of trouble

In most instances, though not all, the mothers say that they saw signs that something was "off" with their sons long before they ran afoul of the law. But they didn't know exactly what was wrong, they say, and they didn't have the resources to get professional help.

Jenny Leavy says that she knew that something was terribly wrong when her son was still a toddler. She was told that he suffered from anxiety and depression, but looking back, she says, it was something else.

"Probably he was somewhere on the autism spectrum," she says.

That was more than 25 years ago, she says, when less was known about autism.

"People had a 'Rain Man' view of it, but he wasn't like that," Leavy says. "I came to believe that there was some kind of problem involving autism because his development was totally uneven."

He was sensitive to certain types of clothing, such as socks with seams at the toes, Leavy says, "he would go berserk."

One of her biggest challenges, she says, was that he didn't look like a child who needed help.

"He was such a cute and charming little kid, and people would say to me, 'He's not that bad, maybe you just don't know what you're doing,'" Leavy says.

But there was one conversation they had when he was about 4 that she says still stands out more than 20 years later.

"He said, 'I'm going to get you fired from your job so we can be together all the time,'" she says. "It was very nerve-wracking because I couldn't get anybody to see this. I was still taking him around to all these different people trying to figure out what was wrong."

One day she ran out of patience with an early childhood specialist.

"I'm not a loud or hysterical person, but I went into this director's office and I said, 'If I come in here with stab wounds and I'm bleeding all over your rug, will you be able to help me then?'" Leavy says.

For some of the other mothers, signs of trouble showed up later.

"They become excellent liars," one mother says. "When drugs are involved, you can't tell when they're telling the truth, so you eventually stop believing anything they say. You don't want to be that way, but you reach a point where you have no choice. And that's sad when you realize you can't believe your own kid."

Others noticed that as their sons reached their teens, they developed a heightened need for instant gratification and took little responsibility for their actions — always, someone else was to blame.

Group leader Karen Cook says that her son was sweet and normal in every way. He was energetic, outgoing, and loved baseball and toy cars, she says.

"When he was 4 or 5, you could take him to the bank, and by the time you were done, he had befriended everyone there," Cook says.

But when he reached junior high school, she says that she discovered that even though he was a smart kid and did exceptionally well in math, he struggled with reading.

"I don't know if it was the learning disability, but he seems to have a hard time even now thinking things through and making decisions," she says. "It's all impulse."

Cook shakes her head.

"It seems to be an issue all the way around with these young men," she says. "They want everything right away. They don't want used furniture or a used car or getting anything that's secondhand. They want everything brand new. They want to go to restaurants and eat expensive meals. They want to have the best clothes, and they want to go on big vacations. You don't start out having those things, but they don't want to earn it."

Cook says that she's increasingly aware of the role that unresolved anger plays in these children's lives.

"I think a lot of young men today are angry because they don't know what direction in life they want to take," she says. "And if you think you're invincible, you think you can get away with doing certain things and taking shortcuts. It's a scheme with them. They're risk-takers and this is what gets them into trouble."

Paying for the past

Plenty of overlap exists between the mothers' emotions; nothing shocks the longtime members. But their emotions do diverge a little between those mothers whose sons are just heading to prison or are already there, and those whose sons have re-entered public life.

Still, it's the diversity of their experiences — the different stages of their grief and acceptance — that gives the group its strength.

The mothers whose sons are in prison struggle to stay in touch with them. The mothers live almost by raw instinct, they say, and they're in a constant state of worry and uncertainty about their child's safety, as well as his physical and mental health.

"My son was showing signs of schizophrenia," one mother says. "He kept talking about this guy named Pauly, and it was 'Pauly told me this and Pauly told me that.' And I started to think, 'Who is this guy that he's taking advice from now?' But there was no Pauly."

Where prisoners are placed is up to the Department of Corrections, and transportation is often a significant obstacle involving long drives for most of the women. Some don't own cars, so they've become resourceful finding ways to get to the far ends of the state.

And almost all of them have travelled to see their son only to be told that he couldn't see visitors that day. And some say that it's not uncommon for prisoners to be moved to different prisons without telling the inmate's family.

"I'm not saying my son didn't do something wrong and shouldn't have been punished," Darlene Morris says. "None of us are saying that. But they sure don't make it easy on the families. And that's the unfortunate part. It's as if we're criminals, too."

Some of the mothers report problems with some of the prison guards. Their sons say that things sometimes get taken from them or that their work detail will be abruptly changed.

Morris says that it's important that the staff at the facility knows that the prisoner has people who care about him.

"The worst thing that can happen is for the staff to think that prisoner has nobody that cares what happens to them," she says. "I made sure they knew who my son is."

Karen Cook's son, Andrew, was released about a year ago after serving nearly a year in a state prison. He's a young man with a boyish face and muscular arms and shoulders. He says that the hardest part about prison is the isolation from family and friends. Andrew graduated from the prison's drug and alcohol program; he calls it a lesson in self-management.

"Many people get kicked out along the way for fighting, stealing, mostly little stupid stuff," he says.

But Darlene Morris's son, Luther, had a much different experience. He was released almost two years ago after serving seven years in state prison. He says that his first prison fight was over a magazine that he returned to the wrong inmate.

"Everything became a crash course for me," Luther says. "I didn't know anything about prison except what I saw on TV."

He says that he didn't want his mother to know what it was really like because it would make her feel worse.

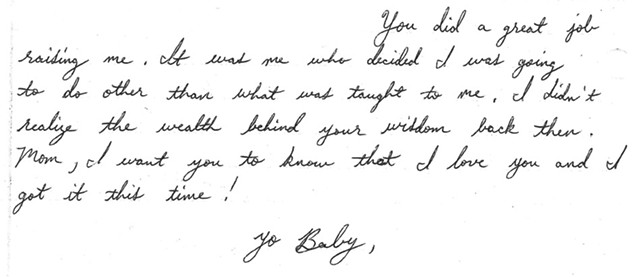

"When my mom came to see me, even if things were going really badly, I would always tell her everything is going well because I could see what it was doing to her," he says. "I would always tell her, 'Mom, I'm fine, don't worry about me.'"

To this day, Luther prefers to have his back against the wall when sitting or standing in a room, he says, so no one can get behind him.

"If you're in a gang, you're going to have it harder," he says. "If you're a snitch or a rapist, you're going to have it harder. If you go in with a tough guy attitude, there's always going to be someone who will challenge you. I made it through. I don't have any scars, cuts, or stab wounds, but I learned to be a light sleeper."

Both men say they can't find the words to thank their mothers for standing by them through their ordeal. And even though these mothers are clearly happy to see that their sons put that phase of their lives behind them, they say that they're still nervous; everyone knows that the recidivism rate is high. It's the elephant in the room.

The joy of being free is tempered by reporting to a parole officer and trying to find a job: a formidable hurdle for almost anybody with a criminal record. Both Andrew and Luther have managed to find work, but it took months and their options were limited.

Even though the country is slowing making steps toward justice reform with movements like "Ban the Box," which prohibits questions about criminal history on employment applications, employers can still conduct background checks.

"It was tough; the background checks are the issue," Andrew says. "I had several job offers. They'd do the background check and then they would deny me."

Andrew has managed to find employment he likes, doing manual labor.

"I think the general public doesn't understand that people make mistakes, everyone makes mistakes," he says. "But the important thing is you can learn from them. You can still be a good person, still be a hard worker, and still be qualified to do almost any job. But this puts a label on you, a very negative label."

He says he lives in fear of even the tiniest slip up.

"Even something minor can send you back," he says.

It's something all of the mothers understand.

Andrew's mother, Karen Cook, says it's an emotional journey from beginning to end.

"There is nothing in the world to prepare you for that day in court," she says.

Speaking of...

Latest in News

More by Tim Louis Macaluso

-

RCSD financial crisis builds

Sep 23, 2019 -

RCSD facing spending concerns

Sep 20, 2019 -

Education forum tomorrow night for downtown residents

Sep 17, 2019 - More »