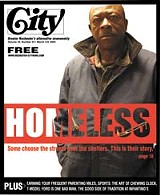

Homeless

Some choose the streets over the shelters. This is their story.

By Christine Carrie Fien (FORMER) and Christine Carrie Fien @CCFien[

{

"name": "500x250 Ad",

"insertPoint": "5",

"component": "15667920",

"parentWrapperClass": "",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

The first car is just a warning, but the cop means business.

The garage-employee vehicle cruised by, blasted a rude reveille, and moved on --- a signal to the sleeping men that it's time to hit the road.

The men rise slowly from the garage floor --- a concrete bed feathered with free newspapers.

"You don't want to smell like urine, especially if you have job interviews," says Charles Kellum, spokesman for the anti-poverty group Poor People United. "If someone peed on the concrete even up to a month ago, if you lay down there, the smell will be on your clothes."

They do this every morning and know they don't have to leave until the cops come. They huddle against a heat vent and wait.

"They've burned all their bridges," Kellum says. "Family kicked them out. Shelter kicked them out. No place to go but here."

Kellum knows. He escaped the streets not long ago and now works to help others do the same. The unknown number of men and women who call the parking garages, the old subway tunnel, and other hideaways in the city's nooks and crannies home, make up the chronically homeless --- those who can't, or won't, get any kind of public assistance.

"There's no sense of time down here," Kellum says. "You just go through the day, hope you can get a good night's sleep."

Kellum doesn't want too much detail about the specific garages the homeless use to appear in the paper. The police tolerate the homeless now, he says. But they might be forced to get tougher if the public finds out where they are.

Kellum has spent many days and nights in the parking garages, sleeping on the floor or hiding in truck beds or underneath cars.

"It's hard for them [police] to see you when this place is filled up," he explains. "You should see when they have a hockey game. People walk right by them [the homeless]. I remember seeing a guy lying down right in front of the doorway. [They] just walked around him. Like he's there but he's not there."

But there are worse things than being invisible. Once, Kellum remembers, two police officers persuaded him to stand beside their buddy's new car so they could take a picture.

"Guess it was funny to have a homeless guy next to his brand new car," he says.

The cop eases his window down, but doesn't speak. James Wilson (names of the homeless in this story have been changed), one-time migrant worker now homeless crack addict, waves.

"Time to go? Alright. See ya tomorrow."

To make sure Wilson and the others are serious about moving on, the cop takes up position toward the back of the garage and watches.

James Wilson started using back in 1995. He buys his drugs, he says, from dealers in the Scio Street area. His addiction keeps him estranged from family and from the assistance he could receive at shelters. He's high, he says, almost every day.

"When I'm on drugs, it changes my attitude. It changes my feelings, it changes my nerves," he says. "I do things a lot differently. It's like, I'm scared. Like people are looking at me in a different way. Like they're out to get me, y'know?"

Most everybody at the shelters uses, Wilson says. And when he's using, he has trouble making curfew.

"I feel bad if I go there when I'm on drugs," he says. "I can't cope with their rules or the people there."

It snowed last night and Wilson, 49, thinks there's money to be made shoveling driveways and walks. But first thing's first: breakfast at the Open Door Mission.

"We don't open till 7:30. You know that," lectures Walt Brundage, grabbing a smoke outside the mission doors. Brundage is the mission's assistant supervisor.

Wilson talks Brundage into letting him in more than a half-hour early.

Breakfast is cereal, bagels, hot tea, and coffee.

The population at the mission is overwhelmingly male. The men eat, sleep, talk, and play cards. The wooden altar becomes a makeshift bed. The canopy is a banner which reads, "Jesus is Lord." The atmosphere is one of depressed hostility. Flare-ups are common, Brundage says, but violence is rare.

"Some are morning people, some ain't," he shrugs. "Most ain't."

It is at the mission that Kellum and Wilson meet up with Arnold Lester.

Lester has been on the streets a week and is barely making it.

"I've been on the streets before, but not like this. This is real bad," he says. "It's cold. I have no family here. I'm very depressed, lot of messed-up thoughts in my head. I really just want to die. I need somebody to talk to me to get on my feet again."

He carries around a package of photographs: him at Seabreeze, hiking in the Adirondacks with friends, flashing a thousand-watt smile in a three-piece suit...

Lester, 41, had been living with his girlfriend and her children in Greece, until, he says, she threw him out. Payback consumes him.

"I just want revenge, you know, when somebody hurts you?" he asks. "I'm very angry with her. I'm so angry. I'm plotting stuff in my head. I want to cut the brake lines on her car. I want her to feel the pain back."

He pulls up his sleeve to reveal what he says are scars from previous suicide attempts.

"I want to die, but I want to hurt someone in the process," he says. "I don't want to go through this pain. This pain is too great for me. I'm ready to snap. She just kicked me out on the streets. She don't give a fuck."

He won't eat.

"How do I know where it came from?!" he says, gesturing toward the food.

Lester's problem, says Kellum, is that he hasn't faced the reality of his situation.

"He was living, like, DVDs, TV, a job and all... All of a sudden now he finds himself without any of those things, and the only thing he can think about is how to get those things back," Kellum says. "That's where the frustration comes in, the anger."

Lester's mood lightens somewhat when he asks Wilson if there's money in panhandling. A practiced panhandler, Wilson usually works the Midtown and Monroe Avenue areas.

"Oh man. Shit, I out there three hours and I had $47," he says. "Back to the Cadillac [Hotel]."

"James always makes money," Lester says. "James, let me get a dollar, man."

Wilson shakes his head.

They're ready to move on, but Wilson needs some supplies first. He asks Brundage for conditioner for his hair, but Brundage's "attitude" ticks him off.

"Yo! If you don't want the job, get out and let somebody else be there!" he shouts.

"It's like he's paying for that stuff," Lester agrees.

The reason Poor People United came into existence is to serve people like Wilson and Lester --- homeless who can't or won't get public assistance.

PPU wants a hypothermia shelter --- a place with limited rules that will take almost anyone.

"We would not restrict people who had been using substances [and there would be] no curfews. No need for payment of any kind," says PPU member Claire Olson. "The only limitation would be disruptive behavior."

Many of the chronically homeless, say Olson and Kellum, refuse to go to shelters because of the rules they impose.

"What we did is, we went down in the subway and we asked these guys, 'Why not go to a shelter?' They told us, 'Listen, we can't handle these curfews. We don't like these admission restrictions,'" Kellum says. "We were able to consolidate that and say... 'Is there any way we can correct this and have a shelter that would allow these people to be served?'"

"What PPU is saying is they want a homeless shelter where they're not going to sniff people's breath and they're not going to wait for [social services] to send money following the head," says Jon Greenbaum, of Metro Justice. "They want a homeless shelter where no questions are asked. If you behave yourself, you get a bed. If you don't, you're shit out of luck."

PPU's efforts have paid dividends. The county now has an emergency hypothermia plan. Several shelters will open additional beds on designated "hypothermia nights."

No set temperature has been established.

"We're kind of using common sense and looking to what the Open Door Mission is doing and the Red Cross, and sort of having a little network... [they] really are the key people to contact the shelters and to contact Lifeline and the missions, and let them know we've activated the emergency system," says County Legislator Carla Palumbo.

Good, says Kellum, but not good enough.

"We've been pushing for this since May. Right now we're seeing some results," he says. "Not everything we wanted, but we see some progress."

There is federal money available for a permanent site. The new shelter, Palumbo says, would be open year-round, 24 hours a day, seven days a week. It would accept sanctioned individuals --- those barred from getting assistance from the county --- and rules would be minimal.

"The concept is pretty comprehensive. It's got loose rules so people can come in at whatever time, day and night," says Ruth Nieboer, director of social services for the Salvation Army. "But it would also have mental health workers, case management, and a lot of services available."

The problem has been finding a location for the new shelter. Whenever a potential site is identified, opposition springs up from neighborhood groups.

"I don't think there's too many communities real excited about having a shelter that predominately targets street people in their neighborhood," Nieboer says.

Donna DeMaria can sympathize. DeMaria is on Albany's Homeless Action Committee, a nonprofit organization "that works to promote permanent solutions to the homeless problem."

Albany has two shelters that operate in the winter only. The committee runs one.

"The term we use is 'a shelter of last resort' for people who can't get into other shelters," because they're drinking, using drugs, or have behavioral issues, DeMaria says.

The shelters, she adds, are "full pretty much every night."

The committee operates its shelter in a Lutheran church. Facing pressure from neighbors, the city, DeMaria says, tried to stop the shelter from opening by denying its zoning permit. But the committee ignored the ruling.

"On the same exact night the zoning board said 'no,' we opened in the church," she says. "Ultimately, they didn't take any action. [Our] attorneys have said that [there is] very solid case law for churches operating shelters."

Every city, DeMaria says, needs a shelter of last resort.

"In every community there is a group of people who can't access the shelters because of addictions, mental illness, just not complying with the requirements of the shelter..." she says. "Then there are people who just won't go because they're afraid, they're paranoid. They're not sure what might happen to them. And some of them have very good reason to be afraid."

Who are Rochester's homeless? They represent a broad spectrum, according to Nieboer. The highest number is single men. But the fastest-growing groups are women, children, and teenagers.

"Some of it's the economy. With teens, some of it is substance abuse," Nieboer says.

In the course of conducting a study late last year, the Homeless Services Network asked homeless individuals where they stay, besides shelters.

"We were pretty amazed by the amount of people who [stayed] in abandoned buildings, in people's garages, anywhere," Nieboer says. "It was just a very high percentage of people who had not stayed in what we consider appropriate places to be housed."

There are about 615 beds available in Rochester, Nieboer says. On any given night, they are 85 percent occupied. Given that there are beds available, Nieboer understands why the county is reluctant to contribute any money toward the new shelter.

"Why open something else when there are beds available?" she says. "Obviously, the county does not have a lot of money these days and they shouldn't use it if they don't have to."

PPU criticizes the county for not contributing any funding toward the permanent site. But the county has provided resources, Palumbo argues, in terms of setting up meetings, enacting the emergency hypothermia plan, and in other ways.

"I think everybody at the table is doing what we can with what we've got," she says. "We just went through a budget where the county cut significant funding for really good programs. I don't think they're going to turn around and come up with any money anytime soon for anybody."

What PPU did, Palumbo says, is bring a critical issue to light and also to offer a potential solution in the form of the permanent site.

"I didn't realize there were people who, even on the bad nights, weren't getting into a place," she says. "I think other groups might learn something: that if you come with a solution you give somebody something to work with at least. I know that this solution [adding beds] isn't everything they wanted. But it was better than not doing anything."

Charles Kellum spent two winters scratching out a living on the streets of Rochester. He slept in parking garages and passed days reading and keeping warm in the public library.

"[They] really don't like the homeless there, but it's a free library," he says. "They won't allow him to fall asleep. They kick him out if he falls asleep. Imagine going the whole day without a nap."

When it is pointed out that many people do, in fact, go the entire day without a nap, Kellum responds, "Really? I need a nap."

Without a permanent address, he couldn't get a library card, so he hid the book he was reading at the end of each day so he could pick it back up the following day.

He spent many mornings, too, waiting for work at Labor Ready on Mt. Hope Avenue. Labor Ready provides temporary workers for manual, skilled, and semi-skilled positions in all industries.

"This is my hustle," he says. "I wasn't good at panhandling. I didn't like looking for bottles. What I do is take a chance, come here every morning."

Through Labor Ready, Kellum, 39, worked construction, did masonry work, dishwashing, and other jobs.

"This was my only source of income the entire time I was homeless," he says. "And I would sit here every day, six days a week. Maybe work twice [a week]."

Kellum's average pay when he did get work was about $35 a day, which he says, buys "nothing but drugs."

"You work so hard. You get so little. It makes you so angry," he says. "$35 is not going to change your life. It's not going to get you out of the street."

He has struggled, he says, with substance abuse and depression. The only thing that kept him going those two years was a primitive desire to survive and the tiniest hope that maybe, somehow, things could get better.

"I felt like, if I'm going to be a loser, I'm going to be a loser somewhere nice, like Florida. That's what my reality was: just make it to Florida," he says.

"There is a hope that you're going to get off [the streets]. What happens is, three, four years pass by without you even knowing it. You don't realize your whole life is passing you by, don't have any kids... All of a sudden I'm an old man. I've got gray hair now."

Kellum was able to get off the streets because a staff worker at the Department of Social Services took a personal interest in him and helped him through the system.

After the Open Door Mission, Wilson heads to St. Joseph's on South Avenue. The restrictions are fewer, Kellum says, and the bathroom facilities are preferable to the mission's.

"The water's much warmer over there," he says.

Wilson wants to clean up a little. It's important to maintain your personal hygiene, he says, because how you're treated has a lot to do with how you look.

"[They] treat me shitty when I'm down and out," he says.

It's also important not to stand out in a crowd. Looking like a homeless person can get you kicked out of places like Midtown.

"Our policy is that there's no loitering in Midtown. If we see someone loitering, whether they're homeless or not, they're asked to leave the mall," says Al Cupo, Midtown property manager. "Loitering is being in Midtown with no intent to shop or eat at Midtown."

"Obviously, it's not a story that we want to see in the newspaper about homeless hanging out at Midtown," he adds. "It reflects negatively on Midtown and it doesn't attract people that we're trying to attract."

Palumbo thinks that as long as Wilson and others aren't bothering people, they should just be left alone.

"If they're just sitting in a chair and being warm, I don't have a problem with it," she says.

Wilson will move from soup kitchen to soup kitchen before returning to the garage for the night. The plan to earn money shoveling snow never materialized.

"They wouldn't have had a good chance," explains Kellum. "They would have to knock on at least 50 or 60 doors and maybe got two or three driveways. It's a lot of work."

Wilson says he will probably pick up a supply of drugs before the day is over."I'm an addict. It's called an addict. I use drugs," he says. "I'm mostly high during the day. It's a very stressful lifestyle."

He has tried to kick drugs many times, he says, but "it only works for a little while."

A tall, African-American man with 10 years of street living clearly etched on his face, Wilson says he knows what it would take to turn his life around.

"Get all the respect. Get a job. Get the welfare. Stay in one place. Clear and simple," he says. "Get the DSS [social services]. Be in the shelter. Do what they tell you."

Is he ready?

"Right now? Today? Yeah," he says.

There's a pause.

"Shit. You know I ain't ready."

Homeless in Rochester, an exhibit of photographs, video, and other visual art by local artists to benefit Poor People United, runs through Saturday, March 6, at The All-Purpose Room, 8 Public Market. The gallery hosts a lecture-discussion on local poverty issues at 7 p.m. on Thursday, March 4. Info and hours: 423-0320 or www.allpurposeroom.org.

Speaking of Homeless, poor People United

-

Feedback 1/7

Jan 7, 2015 -

Is it art or is it anarchy?

Feb 23, 2005 -

Life on the edge

Sep 29, 2004 - More »

Latest in Featured story

More by Christine Carrie Fien

-

Building up

Mar 29, 2017 -

Hetsko's heart

Mar 15, 2017 -

Squeezing starts at GateHouse-owned Daily Record and RBJ

Feb 28, 2017 - More »

More by Christine Carrie Fien (FORMER)

-

Sticking it to the 19th Ward

Apr 21, 2004 -

After Amo

Apr 14, 2004 -

Of bonds, bridges, and bravado

Apr 14, 2004 - More »