[

{

"name": "500x250 Ad",

"insertPoint": "5",

"component": "15667920",

"parentWrapperClass": "",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

Bernie Sanders' presidential campaign is surging. Many media outlets reported late last month that the 74-year-old socialist raised at least $24 million in the third quarter, not far behind the $28 million reportedly raised by Democratic frontrunner Hillary Clinton.

More and more Americans are tuning in to the grumpy grandfather who never strays from his message and who rails against income inequality and the corruption of US politics wrought by the Supreme Court's Citizens United decision. Sanders comes across as stern and sincere, shaking a crooked finger as he insists that only a "political revolution" can save ordinary Americans from the predations of the "billionaire class."

Sanders' popularity has surprised pundits trapped inside the Beltway, but not people closely acquainted with his political biography. They've watched his evolution from a fringe candidate of the far-left Liberty Union Party in the 1972 governor's race, to mayor of the state's largest city nine years later, to his current status as one of Vermont's most popular politicians. Sanders won re-election to his US Senate seat in 2012 with 71 percent of the vote.

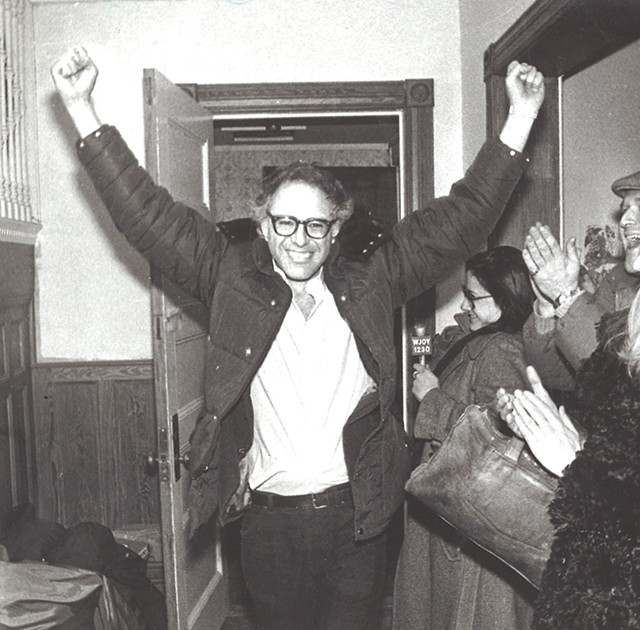

Sanders-watchers say that many of the attributes now becoming evident to voters outside Vermont are the same ones that have helped Sanders assemble ever-broader majorities in the Green Mountain State over the last 35 years. A look at the factors behind his first electoral victory — as mayor of Burlington in 1981 — and his subsequent ascent to the national political scene in the 1990 race for Vermont's sole US House seat helps explain his growing appeal.

Underlying all of Sanders' electoral successes is his ability to win the support of white working-class voters. Sanders' friends, former campaign staff, and academic analysts who have watched him over the decades agree on the elements that comprise his political repertoire: charisma, authenticity, trustworthiness, and simplicity and consistency of message.

Sanders wins respect among moderates and even some conservatives, these sources say, by abstaining from ideology and by taking a pragmatic, but always principled approach to governing and legislating.

"Bernie doesn't talk in terminology laden with Marxist lingo," says Terry Bouricius, a Burlington activist who helped Sanders achieve his upset mayoral breakthrough. "His socialism is more like liberation theology. He speaks about economic injustice as something 'immoral,' not as 'the inevitable product of capitalism.'"

As a candidate who has lost six elections, Sanders has always displayed doggedness and "political fearlessness," adds University of Vermont religion professor Richard Sugarman, Sanders' longtime friend.

Sanders is unintimidated by the forces arrayed against him, adds Erhard Mahnke, another Sanders ally. "People see that Bernie has a fighting spirit, that he means it when he says he's on the side of vulnerable, low-income, ordinary Americans. He's not packaged."

Sanders has also been the beneficiary of sheer good luck, especially in the two pivotal races of his career.

By 1980, Bernie Sanders had earned a reputation as a perennial loser at the ballot box. But University of Vermont political science professor Garrison Nelson recalls that as the Reagan decade was dawning, a perfect storm was gathering in Burlington.

Sanders' friend Sugarman felt the wind shift. He pointed out to his then-39-year-old friend and political soulmate that Burlington had been the source of Sanders' highest vote percentages in the statewide races he had run in the 1970's as a Liberty Union candidate.

Sanders, Sugarman suggested in 1980, should run for mayor against four-term Democratic mayor Gordon Paquette.

"I told him he had a chance, a small chance, to actually win," Sugarman says.

Sanders sympathizers were also galvanized by the election of archconservative Ronald Reagan as president.

Paquette, a working-class Democrat who had compiled a partly liberal record, had meanwhile alienated big chunks of the electorate by calling for a steep rise in residential property taxes. And in what would become an incongruous characteristic of his socialist politics, Sanders was opposed to raising taxes.

In the run-up to the '81 election, Paquette "managed to piss off tenants, the cops, and firefighters," political science prof Nelson notes, by failing to address the issue of rising rents and by opposing pay raises for members of the police and fire departments.

Sanders supported those wage demands, again departing from left-wing orthodoxy — this time by refusing to view the police with suspicion, let alone outright animosity. Sanders would never adopt the '60's leftist rhetoric of cops as "pigs." He instead viewed them as "workers," Sugarman points out.

The Burlington police union rewarded Sanders by endorsing him for mayor of a mostly Catholic and WASP-y city.

"That was the key to the race," says Huck Gutman, Sanders' friend of four decades, who would later serve as his chief of staff in the US Senate.

The insurgent was simultaneously adding to Paquette's political pain by portraying the mayor as a tool of real-estate interests seeking to build high-rise, high-priced condominiums downtown on scenic Lake Champlain.

Sanders' slogan, "the waterfront is not for sale," proved powerful, Sugarman says.

But even with all of these weather systems converging, Paquette might have survived the Sanders storm if he had seen it coming.

"The Democrats didn't pull out all the stops in that race," recalls Bouricius, who has made a career of analyzing election reform. "They couldn't imagine that someone like Bernie could actually win."

A mano-a-mano bout might likewise have ended in a Paquette victory. But as luck would have it, Sanders benefited from a spoiler.

Richard Bove, a restaurant owner and erstwhile ally of Paquette's, had secured a spot on the mayoral ballot out of pique at a perceived slight by the Democratic establishment, Nelson says. Bove got about 400 votes, and "all those votes would have gone to Paquette," Nelson says. Instead, Sanders managed to squeak out a 10-vote victory.

The sort of political revolution that Sanders is urging today actually occurred on a smaller scale in what soon became known as "the People's Republic of Burlington."

Sanders became a hands-on mayor who practiced the principles of "Sewer Socialism." In keeping with the precedent set by a series of progressive mayors of Milwaukee in the first half of the 20th century, he focused on effective and efficient delivery of basic municipal services. Voters also affirmed the radical mayor's affordable-housing initiatives, as his three re-election victories would attest.

"He couldn't be portrayed as a tax-and-spend liberal," Mahnke says. "He was all about making government more efficient and more effective. For him, plowing the streets was a vital responsibility."

Bitterly opposed by the city's Democratic establishment, Sanders succeeded by attracting a set of bright staffers. They were fiercely dedicated to the causes championed by a mayor who was often irascible with staff behind the scenes.

He was soon looking to advance to higher offices. Sanders ran for governor in 1986 and the US House in 1988, but lost both races.

His stage-left entry on the national political scene in 1990 — when he finally managed to win a statewide race — was made possible, in part, by his opponent's blunders.

Incumbent Republican House member Peter Smith, who had beaten Sanders by four percentage points in a six-way race in 1988, alienated many conservative Vermonters, Nelson says, by insulting President George H.W. Bush and by casting a vote that caused the National Rifle Association to campaign against him.

Bush flew into Burlington in the fall of 1990 to help Smith stave off Sanders' challenge. But the intended beneficiary of Bush's benediction proceeded to criticize the president's tax policy on the stage they were sharing.

Smith had also voted for a ban on assault weapons after pledging his allegiance to the NRA's policy of opposing any and all gun-control measures. That spawned a negative ad campaign in hunter-friendly Vermont: "Smith & Wesson, Yes. Smith & Congress, No."

Sanders won the election by a 16-point margin.

The mayor also benefited from the statewide recognition he had gained from earlier unsuccessful runs for governor and the US House, according to then-campaign adviser John Franco. In 1988, Sanders, an independent, got twice as many votes as the Democratic US House candidate. He had proven he was more viable than the mainstream liberal.

"It was the Democrat, not Bernie, who was seen as the potential spoiler in 1990," Franco says. In 1990, Democrat Dolores Sandoval received just 3 percent of the vote.

From there, Sanders would go on to win seven more elections to the House and to score easy victories in races for the US Senate in 2006 and 2012.

Throughout all of his campaigns, the once-obscure outsider never departed from his central themes of fighting economic inequality and calling for reforms that would benefit working-class Americans. Voters who seldom support liberal Democrats let alone radical independents have responded by standing with Sanders.

Mahnke remembers seeing in the 2000 election campaign "Bernie for Congress" signs on many of the same lawns in the state's remote and rural Northeast Kingdom that were also displaying "Take Back Vermont" posters, signifying opposition to a controversial same-sex civil union law enacted earlier that year.

How could this be? Why would many anti-gay rights residents of Vermont's poorest and most conservative region simultaneously support a socialist?

It isn't as though Sanders sends coded signals on cultural and social issues, hinting that he's on the right's side. His record in Congress gets a thumbs-up from groups focused on gender equality and freedom of sexual identity.

It's that Sanders "doesn't foreground those issues," says Gutman, a friend of Sanders.

Nelson agrees, framing Sanders' approach this way: "His politics are horizontal, not vertical. Bernie's class-focused arguments cut across the usual racial and ethnic lines. He's seen, first and foremost, as the champion of the underdog."

During his 25 years in Congress — by far the longest tenure of any independent — Sanders has raised his Brooklyn-accented voice to call for bank reform, a higher minimum wage, and steeper taxes on wealthy Americans. But he has also fought hard for a group rarely associated with socialist views: military veterans.

Although he voted against the war in Iraq, Sanders chaired the Senate veterans' affairs panel for two years — the first time, political science prof Nelson says, that an independent has headed a US Congress committee.

Throughout his full nine-year tenure on veterans' affairs, Sanders has worked to safeguard and improve federal services for former members of the US armed forces, including health care delivered via the Veterans Administration.

He cites the VA's coverage as a successful example of single-payer health insurance.

This involvement with vets is consistent with Sanders' career-long advocacy for the interests of working-class Americans, Nelson says.

"Veterans are mostly working-class guys who depend on federal aid," he says. "It's a perfect cause for Bernie."

That unwavering willingness to stick up for the little guy has won over plenty of conservative voters, Bouricius says.

"I've got in-laws who always vote for Republicans — and for Bernie," he says. "They say he's their guy because he always speaks his mind."

"He doesn't do focus groups," Mahnke adds. "He doesn't raise his finger to see which way the political wind is blowing."

In addition to avoiding leftist jargon, Sanders talks about down-home concerns that many radicals ignore.

"They're into macro," Sugarman says. "Bernard is more about micro. He connects with people on the level of their lived experience — the quality of the schools their kids attend, for example."

Above all, suggests activist and lawyer Sandy Baird, "Bernie doesn't fight the cultural wars. He was never a hippie. He can attract working-class votes because he is working class. He's from an immigrant family that didn't have a lot, so it's clear that he knows of what he speaks."

Sanders has approached legislating in Congress the same way he handled administering a city — by presenting issues as moral choices to be made on behalf of, and with the support of, his constituents.

Today, he's campaigning for the highest office of them all, having launched the Bernie for President drive on the Burlington waterfront.

Initially treated by national political savants as a figure for ridicule, Sanders has again shown that he can surprise those who underestimate him. As was the case 35 years ago in Burlington and 25 years ago in many parts of Vermont, big-dog Dems are saying Sanders has no chance of winning.

His supporters haven't gotten the message yet.

This story was funded in part by Burlington, Vermont-based newsweekly Seven Days, which is chronicling Senator Sanders' political career from 1972 to the present at BernieBeat.com.