[

{

"name": "500x250 Ad",

"insertPoint": "5",

"component": "15667920",

"parentWrapperClass": "",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

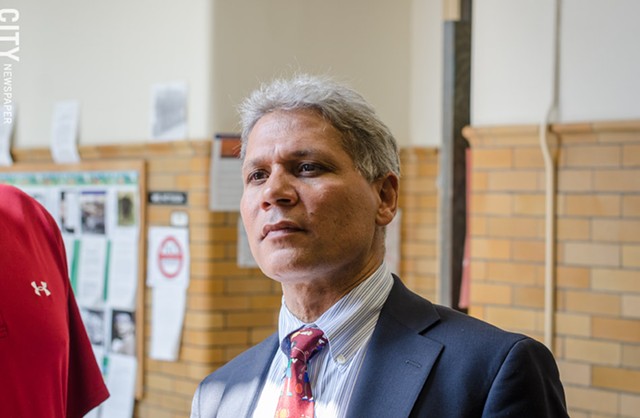

Superintendent Bolgen Vargas's contract with the Rochester school district ends June 30, 2016. While it may seem premature to be thinking about it, the school board will need to have a serious discussion in the next few months about whether to renew that contract or start the search for a new superintendent.

It's hardly a secret that Vargas's relationship with some school board members is seriously strained. If a majority begins to lose faith in him, and they want a successor in place at the start of the 2016-17 school year, they may have to begin the search process in a few months.

Vargas's relationship with some board members has been shaky for a while. But it sank to its lowest point earlier this year when Vargas threatened the board – in essence, his bosses – with legal action. Vargas argued that the board had overstepped its authority when it decided to limit which positions he could hire as top-tier managers.

While Vargas has not taken any further legal action against the board, renewal of his contract isn't guaranteed, and the signs of a break-up are there.

For the district – one of the worst performing in the state – this is familiar territory. Vargas is Rochester's fourth superintendent (if you include Bill Cala's year as interim superintendent) in 13 years. That kind of turnover makes it hard for the district to implement consistent policies and sustain a consistent vision for improving student achievement.

Superintendents in large urban districts tend to change every three to four years, according to some research. No sooner do they settle into an organization, understand the school system, and become familiar with the community, than they're asked to leave – or they move on to a better opportunity.

Some of the turnover may be explained by state education laws. New York, like many states, requires that superintendents' contracts be for a minimum of three years and a maximum of five. Boards can renew the contract, but the structure creates a natural break.

The turnover could also be a reflection of the pressures that come with the job in urban districts – and the difficulty of the job. After 18 to 24 months, a superintendent's strengths and weaknesses are fairly evident. And the clamor for results begins to get louder.

"There's no such thing as a perfect superintendent," says board member Willa Powell. The person you think you've hired isn't always the person you get, she says, and that can be both good and bad.

Board President Van White says that he is not overly concerned by the turnover in Rochester's superintendents. Each superintendent, from Manny Rivera to Vargas, has made contributions, he says. They've come into the district with their own set of skills and experiences, and frequently they were hired to address specific issues of the time, he says.

Vargas, for example, was charged in his first year with stabilizing the district and repairing its relationship with teachers, who had gone through a particularly rocky period with Vargas's predecessor, Jean-Claude Brizard.

But critics, including many parents and teachers, argue that the rotation at the top comes with a cost. Each new superintendent brings a new management philosophy and style as well as new ideas for reform. Some newcomers build on the prior superintendent's work, but some arrive with different priorities.

For instance, Jean-Claude Brizard pushed for a school funding formula sometimes referred to as "equitable student funding." The goal, he said, was to prevent some schools from receiving too much funding and other high-needs schools not receiving enough. Each school was supposed to receive a set amount of funding based more on head count and less on a principal's ability to finesse the system. The plan fizzled with Brizard's departure.

The massive $1.2 billion schools modernization program, begun under Manny Rivera, has also been modified by subsequent superintendents.

Vargas says he's tried to build on the work of his predecessors. Like Brizard and Bill Cala before him, he has tried to change the district's more bureaucratic culture to one that is more focused on parent and student needs.

Still, Vargas faced his own set of challenges when he took over as superintendent. And many of them have been formidable.

"There's no other superintendent in the county and maybe even the state that has been at a greater disadvantage to run a district like this than I have been," he says. And the data suggests he's right.

He started with a graduation rate of 43 percent. Black and Latino male performance on math and reading assessments were some of the lowest in the state. His job was made even harder by the state Regents, who raised the requirements to graduate.

He walked into a district where thousands of students were absent every day, and recordkeeping of chronic absenteeism was abysmal.

He had to continue a school-closing program that began under Brizard – an emotionally charged issue for many students, families, and teachers even when a school isn't performing well.

Vargas also had to begin implementing new state-mandated teacher and principal evaluations as well as the more rigorous curriculum referred to as Common Core. Both remain highly controversial.

But perhaps his biggest challenge was managing one of the largest government agencies in the region. He spoke publicly about denying tenure to principals who weren't cutting it and about his need for management help from area colleges and universities. His openness about the district's bureaucratic problems was praised by some and scorned by others, who saw it as a sign of incompetence.

Nonetheless, Vargas has made some significant headway on some of the district's most entrenched problems. Almost from the beginning, he has said that the district's declining enrollment can be stopped only by improving the schools. And to reach that goal, he's emphasized the fundamentals.

Vargas drew community-wide attention to the district's need to dramatically boost student attendance, improving classroom attendance records, and leading outreach programs, among other efforts. As simplistic as it sometimes sounded, it became a refrain he has repeated often: the district's graduation rate can't improve if students aren't in school.

And he has increased art, music, and sports programs – often standard amenities of schools in middle-class communities – saying they would help students be more engaged in school.

A district-wide emphasis on reading at grade level by third grade became one of his first major initiatives for turning around a failing district. He helped students get library cards, emphasized the importance of parents reading to children, and encouraged parents to create specific places in the home for reading and studying. Once again, seemingly simplistic – but Vargas has been particularly focused on addressing the fact that students in the Rochester school district often lack the bedrock foundations for success.

Vargas's most sweeping initiative has been getting children into the classroom sooner and increasing their instruction time. Among his efforts: launching free pre-kindergarten for all city children.

"This district is the only one in this area that could make this claim: every child that wants a seat in pre-k has one," he says.

He successfully urged the New York State legislature to make enrolling children in kindergarten a legal requirement in Rochester at age 5. And under his direction, 10 Rochester schools offer expanded learning: 300 hours of additional instruction time during the school year. Three more schools will offer expanded learning when school starts in the fall.

And he's tried to close what educators refer to as the summer learning gap – a learning loss that occurs during idle summer months for many low-income students – by offering educationally enriched summer programs.

Is any of this working? Vargas says it's still too early to point to hard data. Expanded learning, for instance, is only in its second year. But Vargas says he notices a change in attitude in students, teachers, and parents in those schools. Attendance tends to be higher, students have fewer behavioral problems, and parents are more engaged, he says. Teachers and staff are also more engaged, he says.

And he points to a graduation rate that has been increasing even as the academic demands on students have grown more rigorous. Last year's graduation rate was 51 percent, certainly still low. But that's up from the low 40's when he took office, and that's significant, he says.

This year's graduation rate is projected to be 56 percent at the low end, possibly closer to 60 percent at the high end, he says.

But some board members haven't been as enthusiastic about that success as others, saying that the improvements aren't all the result of Vargas's efforts. Brizard, for instance, deserves some credit for the improving grad rates, says board president Van White. That rate rose from 39 percent to 43 percent during his tenure.

Vargas's hiring wasn't unanimous; White voted against him, and for at least two other board members, he wasn't the first choice. And for some board members, concerns began to surface early on. For instance, he shocked some of them when for his chief of staff he hired former Rochester Deputy Mayor Patricia Malgieri, a longtime critic of the district.

Tension has also resulted from a sharp difference in opinion about the role of a school board and that of a superintendent. Should the board simply hire a superintendent, set policy and goals, and stay out of the way if the goals are being met? How closely involved should the board be in supervising the superintendent? When does that supervision become micro-management?

In part, that was at the heart of Vargas's threat in February of this year to take legal action against the school board. Under state law, the Rochester board has to approve the hiring of many district employees, including teachers and principals. But on his own, the superintendent can hire some of his immediate management personnel, and the board wanted to be able to approve which positions those would be. For instance, General Counsel Ed Lopez is in that group, but he is the attorney for the entire district, not just the superintendent.

White says the board hasn't been micro-managing operations. And he says it's because the current board has been willing to be more assertive in its supervision of the superintendent that the district is starting to see improvements.

Tension over the superintendent's responsibilities could widen due to a new state education law that gives new authority to superintendents of persistently failing schools. receivership. Under that law, superintendents will have a short time to turn a school around or close it, and their decision won't require a school board's approval.

Another issue: Although they don't say so on the record, some board members question Vargas's judgment and his management skills. There's been substantial turnover, they note, in his senior management team – people whom he himself hired.

And some board members have expressed concern about his conflict with ASAR, the district's administrators union. Contract negotiations between the district and ASAR have been difficult. And some ASAR members were furious when Vargas wanted to deny tenure to some administrators.

Whether Vargas and the board will mend their differences is difficult to predict. The differences are serious, and some strong personalities are involved. If Vargas's relationship with the board sours further, to the point where some members want to buy out his contract, at least four of the seven board members would have to approve. Taking that step would be both expensive and disruptive. So, however, is the continuing tension between the board and the superintendent.

An additional complication: the fall election. The terms of four of the seven school board members expire this year, and one incumbent, Melisza Campos, isn't seeking re-election. So at least one and possibly four members could change. It could be up to a new board to decide whether Vargas is right for the job.

Both the board and the superintendent seem optimistic that the next report on graduation rates will show continued improvement. But that report won't be out until sometime in 2016. And it will take more than one or two positive reports to indicate real, sustainable improvement. Meantime, the board must prepare to make a decision about Vargas's future.

Vargas: 'I'm committed to Rochester'

Rochester schools Superintendent Bolgen Vargas is entering the final stretch of his four-year contract.

But he wasn't new to the Rochester school district or to education in the Rochester area when he was named superintendent. He served on the city school board from 1996-2003, four of those years as board president. And he had been a guidance counselor in the Greece Central School District for 20 years.

He's made some major changes in the district, and there are some indications that the district is finally on the path to improvement. But his problems with the school board have at times become quite public, and have led some observers to wonder if he'll even be here a year from now.

In a recent interview, Vargas talked about some of his accomplishments, but he said he doesn't want to oversell the early results of the work the district has been doing. He acknowledged that he's had some skirmishes with the board, but he said he thinks their problems can be resolved.

And he said he wants to keep his job and continue the work he's started. The following is an edited version of that interview.

CITY: There are indications that the graduation rate will improve significantly for this year. Will we finally break 60 percent?

VARGAS: We do know that we've done better than last year, and last year's on-time graduation rate, which includes summer graduations in August, was 51 percent. That was a five-year high. And we've been able to achieve that even though we have higher standards from the state. Now all students need a Regents diploma, which requires passing five Regents exams.

The potential is there, but I like to under-promise and over-deliver. But given all of the challenges we are facing, I think you'll still see tangible signs that we're moving in the right direction. We're on the right path.

The district has extended the school day at some schools, giving students more instruction time. How many schools have this?

Ten, and next year we'll have 13.

You've said on multiple occasions that extended day is working. What evidence or data do you have so far?

We have some good data, but realize that we are only completing the second year. We'll have even better data soon. But there are different ways to tell if something is working. And sometimes one of the best ways is by looking at the impact you're having on students and families. If you go to School 34, School 23, School 46, or School 10, and you were to ask parents what they think, I believe they'll tell you that's it's working, from their perspective.

They see what makes common sense; we've broken away from giving our students the least amount of instruction time when obviously they need more.

Also, we have attendance improvement and behavior changes in some of those schools that suggest something is working.

It seems that after all the effort you have put into improving attendance – tracking down students, making parents aware of the importance of attendance, better recordkeeping – there has been some improvement in the elementary grades. But there hasn't been much improvement in the upper grades.

That's to be expected. What we're trying to do is break the generational failure that this district has had for the last 30 years.

We know that if you haven't paid attention to the fundamentals like reading at grade level by third grade, making sure that children develop the skill set that's necessary to be successful in high school, they're not going to do well. This includes attendance, because when a child and a family get used to not coming to school in kindergarten, first, second, and third grade, when they enter middle school they'll feel this is the norm.

Prevention is better than the serious level of intervention that we've been required to give. There is a strong association between chronic absenteeism and low graduation rates, because research tells us that unless we turn attendance around, we can't meet our reading goals. They're interrelated.

It's no secret that you've had difficulty with the school board. Has the conflict been about a difference in understanding of roles? The role of superintendent and the role of board members seems to be the flash point. You're charged with implementation. But they're elected, and they're the ones the public points to when things go wrong. Is tension over that just the nature of urban districts?

This is more common in urban districts. And it's happening around the country. But we will come to a joint resolution on this matter. There's no question in my mind about that. The board and I want to move forward in the best way to serve our students.

The board members are definitely the stewards of the organization. There are key areas that they are responsible for. One is making sure that we are spending our money in a very effective way. I think I have helped the board do that well. When I arrived here, we had payroll mistakes costing a half million dollars. I've been able to resolve a lot of those issues.

Policy is the second area where the board is responsible. The superintendent is responsible for implementation. And there is some gray area there, but people will tell you that when you micro-manage the implementation of policies, that's not the most effective way for an organization to be well run. When that happens, normally you run into trouble. And this is not unique to this situation.

Actually, we've had that for many years. I was one of the board members who supported making the roles clearly defined. The way you resolve this in my view is that you have to agree that someone on the operational side has to be in charge.

We've seen our share of superintendents leaving after three years. They make a lot of changes, but they're not here long enough to get much done. I can't think of a highly successful business that operates that way.

When I first went into this job, I asked the board for a five-year contract. I have a four-year contract. You normally begin to see conflict emerge in Year 2. All my colleagues told me to go for a three-year contract, and I told them no, because I am committed to do the work. And no, you cannot do this work in three years.

And I'm not just saying we're on the right track. I'm telling people: see how we're doing. Are we graduating more students? Are we doing more for our students? There's not one person who can argue that we aren't. Are we spending our money more efficiently?

Yet even with unprecedented results, it's difficult to change the culture of the district. It is the most difficult to change and the last thing to change.

When you first started, there were a number of critics who speculated that you would be a co-superintendent with Rochester Teachers Association President Adam Urbanski. But in some ways it turns out that you're in a co-superintendent relationship with some of your critics on the board.

It's an interesting irony. But the only thing I can tell you is that this kind of work requires the ability to work together. Nothing great happens unless you work together. And I strive to do that.

Your contract ends in almost exactly a year. Do you want stay?

I'm 100 percent committed to Rochester. I'm from here. And I've always been committed to Rochester's students, and that will not change.

Are you currently looking for another job?

I've had other opportunities, but that's not my approach to handling things. I am 100 percent committed to Rochester.

Speaking of...

Latest in News

More by Tim Louis Macaluso

-

RCSD financial crisis builds

Sep 23, 2019 -

RCSD facing spending concerns

Sep 20, 2019 -

Education forum tomorrow night for downtown residents

Sep 17, 2019 - More »