[

{

"name": "500x250 Ad",

"insertPoint": "5",

"component": "15667920",

"parentWrapperClass": "",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

It wouldn't take much to convince most New Yorkers — both employees and employers — that they will pay substantially more for health care coverage in 2019 than they do today. But what would it take to convince them that the state could save $45 billion annually in health care costs, while providing all New Yorkers with better care?

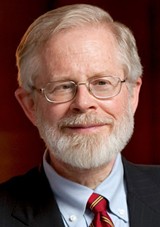

It's been a challenge for state Assembly member Richard Gottfried to muster support for his bill — the New York Health Act — which would bring universal health care to New York by 2019. He hopes that a recent study by the University Massachusetts Amherst will give the bill a boost.

The New York Health Act would save the state billions, the study says, create 200,000 jobs, increase health care access, and provide better health outcomes.

"This is about access to care and quality of care," Gottfried says. "Last year, one in three families with private insurance put off necessary health care due to cost. The New York Health Act would remove the barriers: insurance company bureaucracies whose job it is to say 'no.'"

Enacting this type of plan would reduce economic inequality and eliminate the financial crisis that many New Yorkers experience when health problems occur, says Gerald Friedman, chair of the economics department at UMass Amherst and the author of the study.

Friedman analyzed health care financial plans for several states and says that New York is especially primed for Gottfried's bill because the state's rising health care costs are unsustainable and are driving business investment away.

The NYHA would save roughly $45 billion annually, Friedman says, primarily by eliminating the layers of administrative costs that occur between multiple private insurance companies; the huge amounts of time health care providers spend billing insurance claims; and the need for many employers to administer their company's health insurance benefits.

The savings for employers and employees would be dramatic, according to Friedman's study. For instance, the average annual premium for an employer-provided family plan in New York was about $17,500 in 2013, with employees contributing $4,200 — more than twice what it was 10 years earlier.

And the escalating costs for employees didn't stop with plan contributions. The average deductible on most health care plans doubled from $700 in 2003 to about $1,400 in 2013, the study says.

The other major cost-savings would come from the state's ability to use its purchasing power to drive down the cost of drugs and medical devices, the study says, which are on average 60 percent higher in the US than they are in Canada and Europe.

Friedman says that the Veterans Health Administration saves about 40 percent on the cost of drugs through its buying clout. He estimates that New York would save about $16 billion annually by using similar practices.

New York would see significant economic improvements from the NYHA, as well, Friedman says. While many jobs in the insurance industry would be lost, he says, he estimates that the state would see an overall increase of about 200,000 employees.

"There will be jobs lost in the billing and insurance-related activities in provider offices and in the health insurance industry that sort of take up a lot of energy, but don't really produce anything," Friedman says.

Many of those employees could be re-trained, he says, because the health care industry will continue to grow, and so will the demand for employees.

And lowering health care costs for employers, particularly for small businesses which are hit particularly hard by rising premiums, will allow employers to hire and grow their business, Friedman says. And more entrepreneurs will consider starting a business in New York, he says.

"The big gains will come from New York businesses becoming cheaper to operate compared to businesses in other areas," Friedman says.

Cost savings alone, however, are not enough to fund the NYHA. Universal health care for New York would still require contributions from employers and employees, the study says, but in lesser amounts and without the administrative hassles of the current system. The NYHA would be funded through a broad-based assessment or payroll tax.

Friedman's study suggests that the first $25,000 of a person's income would be exempt from the tax. That would mean that people earning low wages and their employers would pay no tax on those earnings.

The tax would kick in on income above $25,000, and would range from 9 percent to 16 percent, depending on salary. Employers would pay 80 percent and employees would pay 20 percent. Friedman says that most businesses would pay less than they currently pay, and that more New Yorkers would be covered.

Friedman says that most households earning less than $436,000 annually would pay less than they currently pay in premiums, co-pays, and deductibles. And employees would be assured of coverage that is not based on whatever their employer offers in terms of insurance plans, which can vary widely both within a company and between companies.

Improving access to health care is critically important to New York State, Friedman says, because too many people, even after the passage of the Affordable Care Act, have insurance but can't afford to use it.

"There are things that wake you up in the middle of the night," he says. "For me, it's the utilization. People die because they're not getting health care."

But Gottfried's bill has critics. A change of this size and scope is bound to face resistance on multiple fronts. Just the mention of universal health care ignites controversy and conjures up comparisons to socialized medicine and anecdotal stories of poor health care in other countries.

But Friedman dismisses those comparisons as uniformed.

"It's not socialized medicine," he says. "It's completely different from socialized medicine because it is publicly financed, but privately delivered. Britain has socialized medicine. They have a national health service which employs doctors and nurses and provides the services."

Gottfried, the bill's sponsor, says that the health insurance industry and its allies are his most powerful opponents.

"We've also heard arguments about the hypothetical costs of the bill," he says. "This new study answers those arguments."

And there's the challenge of building the political will to pass the bill. Assembly members David Gantt and Harry Bronson are the only Democrats in the Rochester area supporting the measure, so far.

But Gottfried says that the NYHA has strong support from the health care community: pediatricians, family practice physicians, and nurses, as well as some health care union groups. And there is strong public support, he says.

"At our hearings in December and January, we met supporters from every corner of the state, Democrats and Republicans, farmers, policemen, you name it," Gottfried says. "What they all had in common was that they were struggling with high premiums, or limited provider networks, or high deductibles, or any number of other barriers our current system puts between them and their doctors."

Speaking of...

-

Dems are taking a crack at frozen legislation

Jan 23, 2019 -

Feedback 3/14

Mar 14, 2018 -

It's time for Medicare for All

May 10, 2017 - More »

Latest in News

More by Tim Louis Macaluso

-

RCSD financial crisis builds

Sep 23, 2019 -

RCSD facing spending concerns

Sep 20, 2019 -

Education forum tomorrow night for downtown residents

Sep 17, 2019 - More »