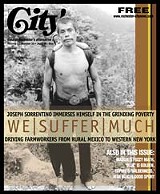

We suffer much

An immersion in the grinding poverty driving farmworkers from rural Mexico to Western New York

By Joseph Sorrentino[

{

"name": "500x250 Ad",

"insertPoint": "5",

"component": "15667920",

"parentWrapperClass": "",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

I'm standing in the back of a camioneta with 15 Mexicans, heading to remote mountain villages in the Mexican state of Oaxaca, when a thought as clear as any I've ever had grabs my attention: "What in the hell am I doing here?"

I'm in the back of that camioneta because I'd written about Mexican farmworkers for City Newspaper and heard stories about the grinding poverty they'd left behind. Many farmworkers in Western New York come from the rural areas of Oaxaca, Chiapas, and Guererro, three states in southern Mexico's "subsistence agriculture zones," according to Bill Abom, Western New York coordinator for Rural and Migrant Ministry.

This means many migrant workers travel over 3,000 miles to get here. Most have paid $2,500 or more to be smuggled in --- a huge amount for people who typically make $600 a year.

Once here, they work on farms in what are arguably the most strenuous, lowest-paying jobs in the US. "I can't imagine the conditions they've left to travel that far, cross the border, and do the most difficult labor here," says Donna Spence, a worker at Migrant Education in Brockport. I decided I didn't want to imagine it. I wanted to see it firsthand.

I've worked in a variety of ways with homeless and poor people in the US. I documented homelessness and poverty across Pennsylvania and Delaware, worked in shelters and soup kitchens, and have spent time in many migrant-worker camps. I even spent six weeks living on the streets of Washington, DC, one winter. None of that prepared me for the poverty I was to experience in the mountains of Oaxaca and Puebla.

It's impossible to get into the mountain villages without connections and a guide. I also learn I need luck and persistence. A combination of all of these lands me in the offices of CEPCO, a coffee cooperative in Oaxaca where I had naively thought they'd welcome a gringo reporter. Instead, I'm met with suspicion and a little hostility.

After three days of showing up for meetings that keep getting canceled, I finally meet with Pedro Pablo Garcia-Hernandez, the secretary of CEPCO. I somehow convince him I'm not a threat and am put in contact with coffee growers near the village of San Jose Tenango (usually called "Tenango").

The initial suspicion with which I'm met at CEPCO is surprising, but certainly not unwarranted given the political climate there. Paramilitary groups are active in Oaxaca, and there are weekly reports of assassinated campesinos (rural workers). "In Mexico, life is cheap," says Jim Breedlove, a friend who has lived in Mexico for 10 years. "And a campesino's life is very cheap." As I leave CEPCO one day, I happen to read a memorial notice on their bulletin board. One of their members had been murdered a week earlier by paramilitary forces.

Candido Morelos Diaz is my guide from the city of Oaxaca to Tenango. The first leg of the trip is a seven-hour bus ride over mountain roads that are little more than narrow hairpin curves carved out of the sides of mountains. It's night when we begin and I'm glad I slept most of the way, because I didn't see how little room there was between the bus and the mountain's edge.

We pull into the city of Huautla at 3 a.m. and sit, in the cold and damp, in the back of a camioneta for two hours waiting for it to fill up before leaving for Tenango.

A ride in a camioneta isn't pleasant. Camionetas are pickups that have been modified to carry passengers, which basically means two metal benches have been welded to the inside of the truck. Eight people can fit snugly in the back, but there's usually double that, with more people riding outside.

The roads, just wide enough for one vehicle, are layered with large rocks. People drive as fast as possible, which insures a jarring ride with your body bouncing off the metal benches and side rails. There are no guard rails on the roads, and although accidents may be rare, I saw two overturned vehicles on the slopes during my travels.

It's a two-hour ride to Tenango. When you arrive, you don't find a quaint Mexican village with a pretty zocalo (town square), colorful market, or distinctive old church. Instead, you're greeted by a small, poor, colorless village, consisting of decaying buildings and a few cement streets that are usually awash in mud. This, I think, is Third World poverty. Turns out I'm wrong. Much worse lay ahead, in the more remote villages.

The trip to San Martin, the first village I stay in, begins with another hour-long camioneta ride followed by a 3 1/2 hour hike, virtually all of it uphill. My guide for this part of the trip is Maximiano, who speaks Mazateco but does know a few words of Spanish. Unfortunately, they are mostly words with which I'm either unfamiliar or can't understand. (These "guides" aren't paid guides, but just someone who's a friend of someone and who happens to be going to the same place as you.)

About an hour into the hike, Maximiano stops for a break. He eats a couple of tortillas and a small piece of meat, and I eat two tangerines. I watch as he fills a Coke bottle with water from a small, muddy puddle and takes a couple of sips.

The trail is made up of rocks stuck in the ground, and whatever isn't rock is usually mud since it's very humid and rainy. When people in Tenango asked if I could hike for over three hours, I told them that I bike a lot in the States and it wouldn't be a problem. I was wrong. The hike is so strenuous that several times I wonder if I'll make it. We pass an elderly woman who is slowly picking her way on the path, carrying a heavy sack on her back.

I arrive in San Martin cold, wet, and exhausted. I'm taken to the house of my hosts --- Abelardo Martinez Guerrero and Ortencia Martinez Figueroa --- and they quickly agree to let me stay, Ortencia bringing me soup when I start shaking. Maximiano continues on to his house, another 20 minutes away. I'm more than a little embarrassed at my exhaustion when I learn he's 72 years old.

I'm shocked at how little he had eaten during the hike: just those two tortillas, a small piece of meat, and a few small bananas we bought along the way. I'm even more shocked four days later, when Abelardo and I hike out of San Martin. Our breakfast before we leave is a cup of coffee.

San Martin is a drab collection of shacks constructed of wood, tin, and palm fronds scattered along the path. The floors of the shacks are packed dirt, and bathrooms are outhouses that are sometimes only a hole in the ground. There is no running water or heat, and nights are cold in the mountains. Children are often barefoot, and animals roam freely. The place smells of mud and manure.

There are a few decaying cement buildings in what's referred to as "El Centro," including a health clinic that's rarely staffed. One evening I ask Abelardo what happens when someone gets sick. He pauses a moment before answering and then says, "When there's no doctor and no money to leave for the city, then you die."

People here know something about death. Candido's wife died 15 years ago. "She had diarrhea and vomiting for several days," he says. "I don't know what it was." Abelardo and Ortencia's four children died soon after they were born. "But I am young," Abelardo says. "There is still time to have children."

San Martin and other remote villages like it in these mountains have always been poor. People here live what is often called "a traditional way of life." That means they've eked out a subsistence-level existence for hundreds of years, surviving on beans, tortillas, and whatever they can pick or dig up from the land. Campesinos here have grown coffee for generations, and it's pretty much the only cash crop that can be grown in the mountains.

"The temperature and the land are good," says Jose Garcia Lopez of Titataniske, another coffee cooperative in Puebla, "but it is too hilly. It is too difficult to cultivate and harvest anything else."

According to Leonor Fernandez Allende, a Regional Director for CEPCO, the majority of campesinos have between one and seven acres of land on which to grow coffee. Ten years ago, that coffee earned about $1.50 a pound, which Candido says was a good price. "I could live well," he says. "At this price I could buy rice, bread, clothes, shoes."

When I arrive in Tenango, coffee is selling for a little under 60 cents a pound. It's now a little under 40 cents a pound. Candido pulls up a pant leg and continues, "Right now I cannot afford socks and do not have any. The clothes I have now were a gift. The shoes were a gift, too."

Felipe Martinez Figueroa estimates he grows about 1,000 pounds of coffee a year. "I earn about 600 pesos (about $55) a month," he says. That's a gross of about $600 a year. Their net is thought to be half that.

"A campesino needs about 30,000 pesos ($3,000) a year to live," Allende says. "To live without hunger, about 80,000 pesos ($8,000)." The truth is that very few campesinos live without hunger. The Instituto Maya, an organization that studies rural issues, estimates that 81 percent of campesinos are "extremely poor," which is defined as earning less than $2 a day. "People cannot afford meat, medicine, or milk," Garcia-Lopez says.

All of the campesinos I talk with grow the basic staples of rice and beans for auto-consumption, but often don't have enough to last an entire year. In previous years, when their supplies ran out, they were able to buy food in larger villages like Tenango. It's different now. When supplies run out, more people are going hungry. "We can't feed our families, our children." says Francisco Martin Julian.

In spite of the poverty and the shortage of food, every family I visit insists I eat with them. There is simply no way to refuse. There are only two meals a day, and they are always simple: usually the classic combination of rice, beans, and tortillas that are made fresh every day (the absolute best tortillas I've ever had). Breakfast is whatever is left over from dinner the night before. Surprisingly, fresh fruits and vegetables are rare.

I tell everyone I eat with that I'm a vegetarian. They find that so interesting that I'm always introduced as: "Jose Sorrentino, a reporter from the United States. He doesn't eat meat." It seems like such a big deal to them that I ask Lucia, one of my hostesses, how often her family eats meat. "Two or three times a month," she says. They apparently can't understand why someone like me, who could eat meat, wouldn't.

It's not as if campesinos are poor because they aren't working. I've actually never seen anyone work so hard for so little. "I work eight hours a day, every day," says Candido. And virtually all of his work is done by hand, his primary tool the machete. At one point I jokingly ask Candido if he has a car. "I do not have a car," he replies. "I am a campesino. I have a machete."

Most of the coffee in these villages is organic and shade grown, so no pesticides or herbicides are used. Clearing weeds using only a machete is long and difficult work. "The weeds must be cut three times a year," says Felipe. "If I cut eight hours a day, six days a week, it will take me one month or more to clear the land." Clearing the land with a machete requires you to stay bent over the whole time.

When the coffee is ripe, usually between November and March, it's picked, washed, and dried, all by hand. This isn't a particularly difficult part of the process, because the coffee beans are collected in small baskets and the distance between the fields and where the beans are stored is generally not that great. But the weather during the day is unrelentingly hot and humid.

In addition to the heat and humidity, campesinos face a number of diseases. I know about malaria, and I'm feeling cocky as mosquitoes buzz by me because I have anti-malarial pills. My cockiness quickly fades when I see warning posters for Dengue fever (also carried by mosquitoes and often fatal), cholera, and tuberculosis.

There are also snakes. I learn about them when one is killed under a wood pile in a woman's house. "Is it poisonous?" I ask apprehensively. "Yes," replies Lucia. "Very." The room I'm sleeping in has a large pile of dried corn. I make sure to keep a safe distance between it and me.

The most difficult part of a campesino's work comes after the coffee beans are dried. Like everything else in these parts, they have to be taken to Tenango. Some people, like Abelardo, are fortunate enough to own a mule, which costs about $300. He loads his coffee on the mule and walks to Tenango with it.

Felipe isn't so fortunate. "I do not have a mule," he says, "I cannot afford one, so I have to carry the coffee. It is a difficult trip. It takes me six or seven hours with a load of 30 to 35 kilos (about 70 pounds). I have to return the same day and bring more coffee the next day."

With coffee prices so low, people are selling what they can. "We grow some beans and corn," Felipe says, "but mostly to eat. When there is enough, we sell it. Beans are 10 pesos a kilo, corn is about two pesos a kilo." That means Felipe may carry a 70-pound sack of corn six hours to Tenango to make about $6.

Candido has tangerine trees growing near his house. During the season, he'll fill up his back pack and sell them in Tenango. I bump into him on market day once. He's particularly happy and I ask why. "I have sold all my tangerines," he says. He'd picked the tangerines, carried a 40-pound backpack 3 1/2 hours to Tenango, and would have to walk 3 1/2 hours back, all for 20 pesos. That's slightly less than $2.

Most people are forced to work at least part of the year away from their homes. Felipe works two or three months a year in Puebla to earn enough to feed his family. "I work in grocery stores, fruit stores, selling clothes, anything," he says. "I can earn 1,000 pesos a month there. Here, I am lucky to earn 600 pesos when there is work."

Candido has two sons, but they work in Mexico City most of the year now. "We did not have enough to eat," he says. "They sell tacos and tortas on the street, 10 hours a day, and make 40 or 50 pesos a day. They also sell sweets. In one month they will return to help with the harvest."

Felipe would stay in Puebla if he could, but, he says, "I can't afford rent, lights, and water."

Facing a combination of brutal work, extreme poverty, and hunger, there's no wonder why more and more people are leaving. "It is difficult to survive in el campo (the countryside)," says one campesino. "This is why people are leaving for Mexico (City) and the US. Many young men are leaving. Some return, but if they have found work elsewhere, they do not return."

I'm told by a number of people that I will find very few young men in the villages. It's not something I'm sure I would've picked up on right away if I hadn't been looking for it. But I'm looking for it, and I can only describe it as strange. There are children, women, and the elderly, and very few men between 15 and 35 years old. The young men I see are mentally or physically disabled or apparently alcoholics.

Instituto Maya is calling it "an indigenous diaspora," the mass migration of people out of the countryside. They report that, since the late 1980s, Mexico has lost almost two million agricultural jobs and 15 percent of its rural population. Men from rural villages have always left for a period of time to work at higher paying jobs. The difference now is that most of them don't return.

When I was interviewing Mexican farmworkers in and around Brockport in 2003, I noted that they rarely complained about their lives. The work they do --- planting, weeding, picking fruits and vegetables --- is virtually all done by hand, in all kinds of weather, and is, by all accounts, extremely difficult.

They live in overcrowded apartments, rundown houses, and, sometimes, in cars or under trees. By US standards, they earn very little money. If they're here illegally, they live in almost constant fear that US Citizenship and Immigration Services will find them and send them back to Mexico.

After spending three weeks in mountain villages, I begin to understand why that is. The danger of presenting information about what it's like in the villages is that some people, like one farmer I've spoken with, will say, "Their lives are so much better here. They're glad for the work."

Yes, they are glad for the work. And, by comparison, their lives are so much better here. But the most common refrain from people when they talk about their life in the village is, "Nosotros sufrimos mucho." We suffer much.

Speaking of...

-

Not all gig workers want proposed protections

Feb 6, 2020 -

County still at odds with its largest union

Oct 26, 2016 -

Fight over schools project highlights divide

Sep 7, 2016 - More »

Latest in Featured story

More by Joseph Sorrentino

-

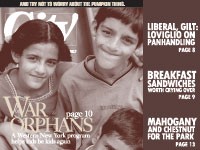

War orphans

Oct 12, 2005 -

Car Zen: the art of mechanical meditation

Feb 9, 2005 -

Life on the edge

Sep 29, 2004 - More »