[

{

"name": "500x250 Ad",

"insertPoint": "5",

"component": "15667920",

"parentWrapperClass": "",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

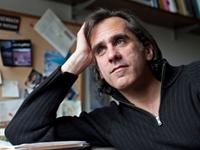

Pedro Noguera began a Ted Talk presentation a few years ago by posing a question parents, teachers, and policy makers have been asking for years: "Why it is that educating children in America has become so hard?"

Noguera, a researcher and UCLA education professor, gives a sharp response: "We have made this much more difficult than it should be," Noguera says.

The problem is not that we don't know how to teach children, Noguera says. There's plenty of research showing what works with every type of child, regardless of their needs.

"The problem is the way we treat children, the types of schools we've created, and the policies we've enacted that drive education," he says. "We have lots of evidence that what we've been doing as a nation isn't working."

Noguera is the author and co-author of several books, including "City Schools and the American Dream: Reclaiming the Promise of Public Education" and "Excellence through Equity." The latter is the theme of a community event hosted by the University of Rochester on Thursday, June 1, where Noguera will be the keynote speaker.

The event, which will be held at East High School at 6 p.m., is free and open to the public.

Much of Noguera's research has focused on how social and economic conditions impact learning. He's devoted particular attention to children living in poor neighborhoods, mostly children of color enrolled in low-performing schools. Though he agrees that many of these schools in cities all across the country are failing, particularly at educating young black males, he parts company with the education reformers who believe that poverty doesn't matter and schools should be able to do the job.

"No Child Left Behind did a good job of illuminating where there were problems in public education, exposing the gaps in achievement that we now know are pervasive," Noguera said in a recent telephone interview. "But what it didn't do was support the schools on how to close those gaps."

The strongest indicator of how a child will do in school is family income, he said.

And, he said: "When you combine family income with parental education – how much education the parents have – that's the strongest driver of student outcome."

So instead of asking how we hold teachers accountable or how we close the achievement gap, we should be asking different questions, Noguera said.

"How do we create schools where a child's race or class does not predict how well they will do?" he said. "I think the mistake we've made is to blame teachers and not look at whether those schools have the adequate resources to meet the needs of their students."

Put another way: How do we create equity for every student and every school? "The only thing that is going to lead to more equity is high quality schools," he said.

In "Urban Schools and the Black Male 'Challenge,'" one of his papers, he debunks the idea, a favorite of reformers, that schools alone can mitigate the impact poverty has on children through rigorous instruction.

He cites a 10-year study from the University of Chicago that examined the typical No Child Left Behind reform formula: closing failing schools and making massive investments in technology and professional development. The researchers found that "problems related to poverty – crime, substance abuse, child neglect, unmet health needs, housing shortages, interpersonal violence and so forth – were largely ignored," Noguera writes. And the results, in the form of academic improvement, were limited.

Noguera isn't anti-charter school, and he knows that Rochester has some high-performing charter schools. But on average, the student outcomes for most charter schools are not that different from traditional public schools, he said in the telephone interview.

"The kids that are most disadvantaged often aren't in those high-performing charter schools," he said. "You have kids that are homeless and in foster care, and these kids require more services."

And if charter schools continue to proliferate at their current rate, they will leave traditional public schools with the most expensive and challenging students to educate, he said. Poor children living in poor neighborhoods are still going to be segregated by race and class, he said.

"The effects of poverty show up at childbirth and even before, when the mother is pregnant," Noguera said. "We can support schools with a comprehensive array of services that include things like mentors, social workers, parent education, and other supports."

The Harlem Children's Zone in New York City, with its wrap-around care for low-income children and families, is the best model of this, he said.

"It's shown that you get much better results with these supports," he said. "What I think we need is a more comprehensive approach, where we're thinking of partnering not just with universities, but hospitals, non-profit agencies, and churches to help schools address some of the issues around poverty that schools can't handle by themselves."

Noguera's talk coincides with the Rochester school board's decision to enter into a partnership with SUNY Geneseo to manage School 19. The relationship would be similar to the one the board entered into with the UR's Warner School of Education and East High. The hope for the partnerships is that by bringing the right combination of resources into the schools, some of which specifically address poverty, student performance will improve.

The challenge for Rochester, Noguera said, "is figuring out how to do this for the greatest number of schools."

Noguera isn't timid talking about the higher costs involved in educating poor children in comparison to suburban children from middle and upper-income households. It does cost more money, he said.

"On the face of it, it would seem like Rochester is well-financed," he said. "It has higher than average teacher salaries and per-pupil spending that is much higher than in many other cities. However, most of the money is not going to issues that address poverty. There is still a shortage of social workers, and there's still a shortage of high-quality pre-school and after-school programs."

It's great that organizations like the UR can bring some of its resources to a school like East High, Noguera said. But the issue that the Rochester school district is facing is one that many districts across the country still end up facing: what about the other schools?

"You know we live in a country that's still rich," Noguera said. "If we're creative about how we make resources available to our neediest schools, we could do a much better job of helping to compensate for the effects of poverty."

Speaking of...

Latest in News

More by Tim Louis Macaluso

-

RCSD financial crisis builds

Sep 23, 2019 -

RCSD facing spending concerns

Sep 20, 2019 -

Education forum tomorrow night for downtown residents

Sep 17, 2019 - More »