[

{

"name": "500x250 Ad",

"insertPoint": "5",

"component": "15667920",

"parentWrapperClass": "",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

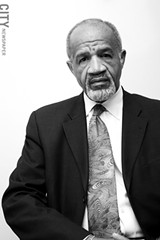

The Democratic primary for the State Assembly's 137th district is sure to be a referendum on the long career of incumbent David Gantt.

Gantt has represented the district for more than three decades. On September 13, voters will decide if they still want or need the influence Gantt's seniority offers, or whether the district is ripe for a fresh face.

Gantt is in a three-way Democratic primary against Rochester school board member Jose Cruz and Monroe County Legislator John Lightfoot.

Cruz and Lightfoot are brand names, or close to it, in Rochester, but election odds typically favor incumbents. Gantt, who agreed to be interviewed for this article, but later cancelled for health reasons, has many loyal followers. There's no questioning his record of service: he has brought millions of dollars to Rochester and helped many projects come to fruition.

But he has many detractors and critics, too; merely mentioning Gantt's name can draw strong reactions. Some of his critics would not speak on the record for this story. But any politician who has survived as long as Gantt is bound to stir controversy and make a few enemies along the way.

Gantt plays to win. The dean of Rochester's state Assembly delegation, Gantt is arguably the most powerful politician in the region, and only the most naïve newcomer wouldn't be a little nervous running against him. Gantt ran unopposed in his last two elections, and it will take a lot of work and a bit of luck to oust him.

Gantt's district includes a portion of the northeast section of the city, downtown, and some of the southwest neighborhoods. Then it stretches westward until it picks up the Town of Gates.

The 137th District, formerly the 133rd, includes some of the poorest ZIP codes in the state and is often associated with dire public health statistics. The district is largely black and Latino, but also includes the Town of Gates, a largely white middle-class bedroom community.

That Gantt is revered at one end of his district and almost ignored at the other is not surprising. His commitment to Rochester's poorest communities, where he is a beloved patriarch, seems to define him personally and professionally. He is a pillar of hope in an area of the city where hope is often in short supply.

To his political allies, Gantt is an old-school politician: instinctual, generous to his supporters, and as fierce as a lion protecting his den. But to his critics, Gantt is a career politician, known as much for his mercurial temperament as his statesmanship. He's crafty, and he can be intimidating. He doesn't take criticism well, and he has no qualms about confronting his opponents. He is infamous for losing his temper with reporters.

But whether you admire, fear, or revile him, there's no denying that the enigmatic Gantt is a giant and a pioneer. He didn't open the door to politics for African Americans and other minorities in Monroe County — he helped kick it down.

Gantt seems to live by his convictions. Though he could probably afford to live just about anywhere in Monroe County, Gantt hasn't ventured far from one of Rochester's most impoverished areas where unemployment, violent crime, and drug-dealing are persistent problems. He lives in a two-story house sitting on a one-way street just off East Main Street. His back yard overlooks the Inner Loop and the hum of passing cars and trucks is constant. A blue vinyl house at the end of his street is boarded up and abandoned, and the next street over is pocked by vacant lots.

Gantt credits his interest in public service to his mother, Lena Gantt, a well-known community advocate in her own right. City Council President Lovely Warren, a Gantt protégé, says Gantt's long career is due to one thing: putting the interests of the community before his own.

"I think he represents his constituents well," she says. "He was elected to serve the underserved community. And I believe throughout his political career he served those individuals, and made sure that resources and other things were extended to those places that would not otherwise have been there."

Gantt is chair of the Assembly Standing Committee on Transportation, and chairs both the Assembly Subcommittee on Affordable Housing and the Subcommittee on Voter Registration. But he began his political career on the ground floor. He served as a Monroe County legislator for nine years, and initiated the federal redistricting lawsuit that resulted in the creation of the 133rd Assembly District. In 1983, he became the first African American from Monroe County to win a state office.

City Council member Adam McFadden calls Gantt a trailblazer.

"We [the city's minority community] were represented in Albany for the first time," McFadden says. "A lot of people don't know that. It wasn't that long ago, either, that we didn't have a voice."

Gantt's representation of the minority community is important in another way, McFadden says. His success created opportunities for minorities interested in politics, including Warren, city school board member Cynthia Elliott, and New York State Regent and former City Council member Wade Norwood, to name a few.

"He's earned a lot of respect from all minority elected officials," McFadden says. "I would say some debt is owed."

Warren says some projects transformative to Rochester, such as the multimillion-dollar Brooks Landing riverfront development — couldn't have been done without Gantt's efforts.

"There was for a number of years a standstill because of things that were going on with [the state Office of Parks, Recreation, and Historic Preservation] and state regulators around building on the waterfront," Warren says.

The Genesee River stood as a physical and symbolic barrier between the University of Rochester and its neighboring minority community. Council members McFadden, Dana Miller, and former Democratic County Legislator Calvin Lee stressed to Gantt that the project was important to 19th Ward residents, Warren says.

"Had it not been for [Gantt's] advocacy in Albany, that project would not have ever happened," she says. Gantt helped the developers navigate the regulatory hurdles and got the project moving forward, Warren says.

Gantt also helped get funding for the Frederick Douglass-Susan B. Anthony bridge, a major construction project that transformed the city's skyline. And he's secured funding for numerous road improvement and housing projects.

And Gantt has been one of the area's strongest education advocates from early childhood to college.

"He's probably the city's greatest champion for the Rochester school district," McFadden says.

Gantt helped get $325 million in state funding for the first phase of the massive remodeling of Rochester's aging school buildings. The project is expected to cost $1.2 billion over 15 years, making it one of the largest construction projects in Rochester's history.

After years of planning, workers broke ground on an addition for School 50 earlier this summer, officially launching the project.

Examples of Gantt's generosity on a personal level are not hard to find, either. The Rev. Ray Scott, a longtime activist who has known Gantt for nearly 40 years, says Gantt gets requests for help almost every day. People seek the Assembly member's assistance on everything from discrimination cases to problems with the DMV to support for new legislation, Scott says.

"There are so many things he's done and people he's helped out of his own pocket that people will never know about," Scott says. "He just gave a young woman from the community a scholarship for college. He doesn't even know her. He's never even met her."

And when Theresa Bowick wanted to start a simple fitness routine for children and adults living in the Conkey Avenue neighborhood earlier this summer, she turned to Gantt for help. Bowick came up with the idea of the "Conkey Cruisers," a group of residents who could meet for regular bike rides to increase physical activity and help with weight loss. Gantt purchased 10 new bikes for the Cruisers, Bowick says. Some of the residents had never owned or even ridden a bike, she says.

"We couldn't do this without Mr. Gantt's help," Bowick says. "It may not seem that important to someone who doesn't live here, but we have the highest rates of hypertension and diabetes in the 14621, 14605, and 14609 neighborhoods. Mr. Gantt immediately understood how serious this is."

But despite Gantt's accomplishments, his critics say he is not always the benevolent political leader his supporters portray. He's been accused of using his influence to reach into the affairs of both city government and the school district.

And some critics say his attention is too narrowly focused.

"I'm sure David, in his heart, is more interested in what we do for building up neighborhood rec centers than he is maybe about what I'm doing for Midtown," says Mayor Tom Richards. "But he's never come to me and said, 'Stop doing Midtown.'"

And Frank Muscato, chair of the Gates Democratic Committee, says that, overall, Gates residents feel neglected by their state Assembly representative.

"If you go back in history, he has brought a lot of money to the Town of Gates," Muscato says. "But he hasn't been very visible."

Muscato says Gates voters have a sense that Gantt doesn't take the concerns of his suburban constituents seriously.

"I think he has much more interest in the people in the city," Muscato says. "But as I've pointed out to him and Lovely Warren, we have the largest nonwhite student population. We have a growing population of students who qualify for free and reduced meals. We need his help, too."

Muscato says Gates Democrats met with Jose Cruz and John Lightfoot, and that this is the first time in 30 years many voters are seriously considering alternatives to Gantt. Many are willing to take a chance on voting for someone else even if they risk angering Gantt because they feel they have nothing to lose, Muscato says.

"I've had people say they won't put up David's sign," Muscato says. "I'm not trying to trash the guy, but we're just not that significant to him."

Ralph Esposito, retired Republican supervisor for the Town of Gates, says he worked well with Gantt in the 1970's, but then Gantt got the "Albany disease."

"He forgot about us," Esposito says. "David, as far as I can remember over 21 years, appeared in Gates maybe twice, maybe a little more. He's been invited to many town functions, but never comes out here. Criticism of him is certainly warranted in Gates."

Something is wrong when a representative hardly ever sets foot in one part of his district, Esposito says.

But Esposito also says that Gantt was instrumental in the creation of the new Westgate Park, which required state legislation.

"David said, 'If Ralph thinks it's a good idea, I'll go along with it,'" Esposito says. "I've always said that I don't know of any Democrat who would have gone along with a Republican then. He took the call."

And Gantt caused a flap in 2008 when he introduced a bill authorizing Upstate use of red-light cameras — after years of opposing them. The legislation "seemed to benefit a client of lobbyist Robert Scott Gaddy, Gantt's former aide," wrote Joseph Spector of Gannett News Service in 2008.

Some of the worst criticism of Gantt comes from the Rochester school district. Gantt has been a harsh and vocal critic of the city school board, and he supports mayoral control. He revived the contentious issue recently though it bitterly divided the city the first time.

"This board has failed," Gantt said. And he promised to reintroduce legislation to pass mayoral control even though Mayor Richards, unlike his predecessor, now Lt. Governor Bob Duffy, isn't enthusiastic about the idea.

Dragging the mayoral control issue back out seems like a pointless distraction to some observers — something the troubled school district doesn't need. And heaping all of the blame for the district's poor performance on the school board and the teachers union seems to ignore other underlying causes, like extreme poverty and troubled neighborhoods, critics say.

But the pushback didn't dissuade Gantt. The board and school officials have tried it their way for years, Gantt said in an interview with City last year. He said he could no longer stand idle and watch more students fall through the cracks, fail to graduate, or graduate from city schools without the skills needed to succeed in college.

When asked why he believes mayoral control would improve student performance when the record is mixed on its success in other urban school districts, Gantt said he didn't know if it would work in Rochester. But the current system hasn't worked for years, he said, and he is willing to give mayoral control a try.

Gantt also called for the elimination of the Maintenance of Effort law, which locks in a minimum yearly payment of $119.2 million from the city to the school district. Like other city leaders, Gantt says the MOE stresses the city's finances without giving the city any say in how the money is used.

Still, many of Gantt's supporters believe he was right to call for mayoral control, though the legislation he promised last year never materialized.

Regardless of where people stand on mayoral control, it got the community talking about education, says Council member McFadden.

"It made us think about how much we value education in our community," McFadden says. And he says Gantt deserves credit for trying to keep the issue on the table.

The other criticism of Gantt that seems to resonate with many of his critics has to do with the city's crescent area. Gantt has represented some of the most impoverished neighborhoods in the city for 30 years, and there's been arguably little improvement.

But McFadden says that is a straw-man argument.

"I think that's bullshit," he says. "One person doesn't control what's going on in his neighborhood or the crescent. I think that's laziness when they say stuff like that. As bad as things are, just imagine what things would be like if he hadn't been there."

If there is a central argument to make in support of Gantt, it hangs on that query: What would Rochester be like without him? And Gantt doesn't make it an easy question to answer; his disposition sometimes gets in the way.

"There are a lot of different opinions about David," Mayor Richards says. "This you've got to say for him: the guy is committed to the city. You may not like his style, you might not like some of the things he does."

But Gantt's support can make the difference on whether a project or funding gets approved in Albany, he says.

"When I want something out of the Assembly, it's very clear to me that I've got to try to get him to go along," Richards says.

Includes reporting by staff writers Jeremy Moule and Christine Carrie Fien.

Speaking of...

Latest in News

More by Tim Louis Macaluso

-

RCSD financial crisis builds

Sep 23, 2019 -

RCSD facing spending concerns

Sep 20, 2019 -

Education forum tomorrow night for downtown residents

Sep 17, 2019 - More »