[

{

"name": "500x250 Ad",

"insertPoint": "5",

"component": "15667920",

"parentWrapperClass": "",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

Painting new portraits of mental illness and HIV

There's a semi-secret, makeshift artist's studio tucked away in a sunny office beyond the labyrinth of labs and offices of the University of Rochester's Medical Center. There, Charmaine Wheatley has set up camp since January 2017, when she came to Rochester to paint two extensive series of portraits of individuals from two stigmatized communities: people living with mental illness, and people living with HIV. Her residency concludes April 30, and will culminate with a traveling exhibition.

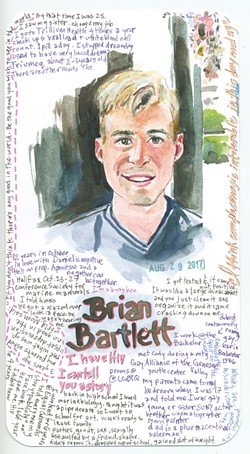

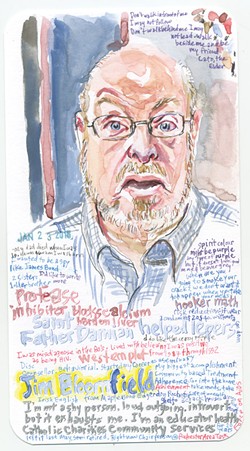

Wheatley describes her project, "Humanizing is Destigmatizing," as an artistic endeavor to reduce the stigma surrounding mental health and HIV. Toward that end, she's created scores of small watercolor and ink portraits of people in both communities, each about 7 inches tall by 4 inches wide, with the person surrounded by hand-written phrases and quotes that Wheatley pulled from conversation while sketching each subject. By combining the portraits and the words, she's trying to paint a fuller, more intimate picture of the diverse set of stories — the struggles and triumphs alike.

There's a wealth of content in the jumbled cloud of words that surrounds each figure, and much like getting to know a person, there's something new to learn each time you revisit the image.

The subjects in the portraits are facing forward, sometimes caught in mid-speech. Despite the difficult subject matter, there's an overall tone of dignity, optimism, and a bright vitality in each of them. And the diversity shown in both of Wheatley's series promotes the understanding that these issues can impact anyone; her subjects are someone any of us know.

Wheatley's Med Center studio serves mostly as a planning and portrait-finishing space, because she does the bulk of her work out in the field, sitting knee-to-knee with her subjects while she talks with them, learning their stories and studying their features. The tables in her studio are strewn with paintings she has yet to complete. Some faces are vague, color-blocked forms that she'll resolve into identifiable features, and clusters of penciled phrases will be pushed and pulled to gain greater prominence or subtlety.

"Poor Kate doesn't have a nose yet," she says while lifting one of the unfished works. "I take snapshots, too, toward the end of the session, and work from those later. But I try to focus on the way you look at first, and as we become more comfortable with each other, I find that you'll open up and say things, once you realize I'm not here to judge and I think everything that you are is fantastic."

A dry-erase board facing the large windows is filled with names — each receives a check mark when the portrait is complete — lovingly spelled out in elegant script.

Wheatley is a painter and performance artist originally from Nova Scotia. When she moved to New York City more than two decades ago, her art evolved drastically.

"Back in Nova Scotia, it's quiet," she says. "I can have like eight or 10 hours of uninterrupted time to paint. And that's great for doing oil painting, but then I moved to New York, and eight or 10 hours of uninterrupted time is not possible, so I evolved my working method."

She began taking a party-favor watercolor set on the subway and creating small portraits of people and recording notes on scraps of paper. "I have many boxes full of drawings and notes, because everything is interesting, and it's overwhelming, so I was trying to nail down as much as possible," she says.

"I like hanging out, but you know, that looks slack. So if I have these little tangible moments...." she trails off. She keeps the paintings in pocket-sized tin boxes that she can easily slip into her purse. "It's important to keep it portable" she says. "It's a the-world-is-my-studio kind of thing."

Wheatley's portrait practice gradually coalesced into different series. In 2016, she took part in two SU-CASA artist residencies (a community arts engagement program through the Brooklyn Arts Council), painting portraits at Polish and Latinx senior centers.

"Some people didn't speak a lick of English," she says, "and we figured it out. We had translators, and I would make art with them. I think it was really nice, especially for seniors — I think a lot of seniors can feel invisible. They exist, and they're important. Every time I'd ask, 'Have you ever had your portrait done,' and everybody says, 'no,' so there's this beautiful connection."

It's atypical for the Med Center to host an artist in residence. The Rochester-Buffalo project was initiated by Steve Dewhurst, vice dean for research and professor and chair of microbiology and immunology at the University of Rochester's School of Medicine and Dentistry. Dewhurst is also an art lover, and he became aware of Wheatley's tiny portraits during a visit to Boston's Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, where Wheatley became an artist in residence in 2012.

"I live at the museum," Wheatley says of the Gardner, which is housed in an old mansion adjacent to the Massachusetts College of Art and Design. "One time, for the course of a month, I would sit in their living room, and people that were coming to the museum could sign up and sit with me for 30 minutes. That was 104 portraits. And then I did it a second time."

"They had an exhibit of her work, which I just really liked," Dewhurst says. "I asked Charmaine if she'd ever done portraits of people living with mental illness. I have personal family interest in that area."

At the time, Wheatley says, she thought she probably had made some portraits of people with mental illness but hadn't done a project under that specific umbrella. She kept in touch with Dewhurst via email, and within a few months she expressed an interest in setting up a residency or fellowship in Rochester.

"What I liked about the work is the combination of the images and the narrative content," Dewhurst says. "They're not people telling stories, but they're intimate moments. So you get a sense of the person in a way that you don't typically get with a portrait. It's much richer. And because they're fragments of conversations, they're also open-ended."

understanding of the inner life of the people who surround us.

Award-winning filmmaker Don Casper created a documentary on each of Wheatley's series: "Portraits of Life" about the mental health series and "Don't Define Me" about the HIV series.

Dewhurst was familiar with some of Casper's previous work, and reached out to him about possibly doing a film on Wheatley's mental illness series. "We talked about creating a small film that would document the whole effort, looking at her process and all that," Casper says. "For that film, we spent an entire day, filmed her painting a few portraits and sitting down with people who had just had their portraits done. I approached it kind of as a portrait of somebody making portraits."

"Portraits of Life" was screened at Canada's 2017 Bluenose-Ability Film Festival, where it won Best Documentary award.

As Wheatley began developing her HIV series, Casper returned to document the process for a new film. A showcase of a selection of the HIV paintings was held on March 15 at Arbor Loft, and portrait subjects from Buffalo and Rochester attended. Casper screened his film, "Don't Define Me," which will be available to a wider Rochester audience on Saturday, April 21, when it receives its world premiere at the Little Theatre during Rochester's One Take Film Festival.

Wheatley's subjects hold the viewers' gaze and communicate the fact that disease is a part, but not the sum, of being human. And through the text, viewers also gain glimpses of progress made and wisdom gained and incorporated into the individual lives.

Importantly, Wheatley wants her subjects to participate in their own portraits. "What you give me during that time that we're together, I'm trying to get as much of that as possible," she says. "I'm looking for what makes you you, what's your unique character."

When Wheatley speaks, she exudes sincerity and enthusiasm, her eyes wide with wonder. She rarely breaks eye contact and smiles warmly and at times conspiratorially, making it easy to feel relaxed and open in her presence.

But understandably, there have been instances where she had to work more extensively to draw people out of their shells. One of these subjects was Sabrina, who is included in the paintings of the HIV community.

"After I did her portrait, I met with her three more times to see if there was something I could do to ease her tension," Wheatley says. "She was fine with her image, her face, and she brought this fantastic blouse. She liked her portrait. But having elements of the dialogue in the portrait: for me that adds richness. You're not just a pretty face, you're much more; you're a struggling human rising above.

"But still, I think we make progress every time that we speak, especially if there's time in between, because things become more comfortable. She's had some hard times. And maybe it's hard to remember or acknowledge that this is a different time that you're in. You've grown and gleaned wisdom from those hard times. You're not gonna play it the same way. You're stronger now."

With another subject, Jazzelle, "we didn't talk about HIV whatsoever," Wheatley says. "Sometimes it just doesn't come up. And then we were having this event, and were putting these huge banners up in the Flaum Atrium — and I realized that her portrait had no HIV content whatsoever. So I called her, and I added something."

Wheatley created a second portrait of Jazzelle while Casper was filming his documentary on the project. She says Jazzelle told her that "she didn't initially discuss her HIV-positive status because, 'already being trans and black, I feel like nobody's going to love me. And then add HIV — impossible.' But what really happened is that she's more loveable," Wheatley says. "The more we can accept ourselves — it's inspiring, and you want to be around that."

Wheatley's mental health series was created between January and July of 2017 and includes about 75 portraits of people from the Rochester community living with mental illness as well as those of professionals working in the field. And sometimes there is some crossover within one portrait, she says.

Wheatley began her current series of portraits of people living with HIV in Rochester and Buffalo in August of 2017. She linked up with individual subjects by working in collaboration with the Rochester Center for AIDS Research and with Evergreen Health in Buffalo. When the project concludes, she estimates, there will be about 114 portraits.

"One thing that's really nice is you do these portraits of individuals, but then it unfolds into a portrait of a community," Wheatley says. "And then you see connections crossing over, which becomes this beautiful weave."

The mental health community and the HIV community experience different shades of stigmatization, Wheatley says. With HIV there's still a sense of fear; she's learned, she adds, that to have HIV is to be an activist, and that there's a strong sense of family within the HIV communities.

"Within mental health, there's still so much mystery around it," she says. "Why do we have such a difficult time sometimes, and other times we feel ok? What are the triggers? It's more vague, and there's such a broad spectrum" of illnesses. "At least it seems that way. I'm not a scientist; I'm an artist just making observations."

One of her subjects said that he told Wheatley things he hasn't told a psychiatrist in 30 years, Dewhurst says. Turning to Wheatley, Dewhurst continues: "And that's the thing: you were saying most people haven't had their portraits done, but they also haven't really been listened to, not really. That's very powerful, that a lot of the people who have sat with you have stayed in touch."

Wheatley is planning to turn the two series into artist's books. She'll make reproductions of each set of paintings and offer them for sale in limited-edition boxed form. And the two finished bodies of work will be exhibited in a to-be-determined location. She envisions touring the work to different cities, accompanied by Casper's documentaries and context provided by people working the mental health and HIV fields.

"I hope there's no end," Wheatley says of her portrait series projects. "I've fallen in love all over the place."

Learn more at artreducingstigma.com.