[

{

"name": "500x250 Ad",

"insertPoint": "5",

"component": "15667920",

"parentWrapperClass": "",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

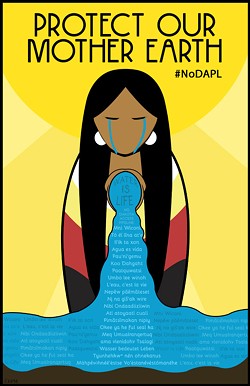

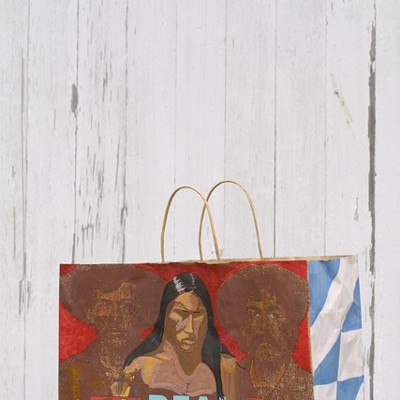

This time last year, art therapist Lauren Jimerson and her teenaged son, Angel, traveled to North Dakota to stand against big oil with the Indigenous community at Standing Rock Reservation. They were two of many Seneca Nation members who expressed solidarity through their presence, protesting the Dakota Access Pipeline, and helping feed the thousands of people gathered in the makeshift village camps. They brought Iroquois White Corn and squash, and Jimerson documented the scene with her photographs. A year later, some of her images along with resistance poster art by other Indigenous artists are part of a show she's curated that is currently on view at Mercer Gallery.

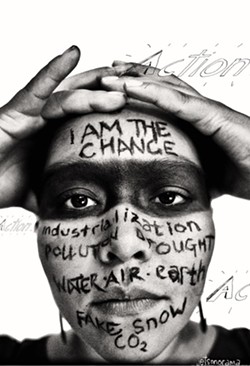

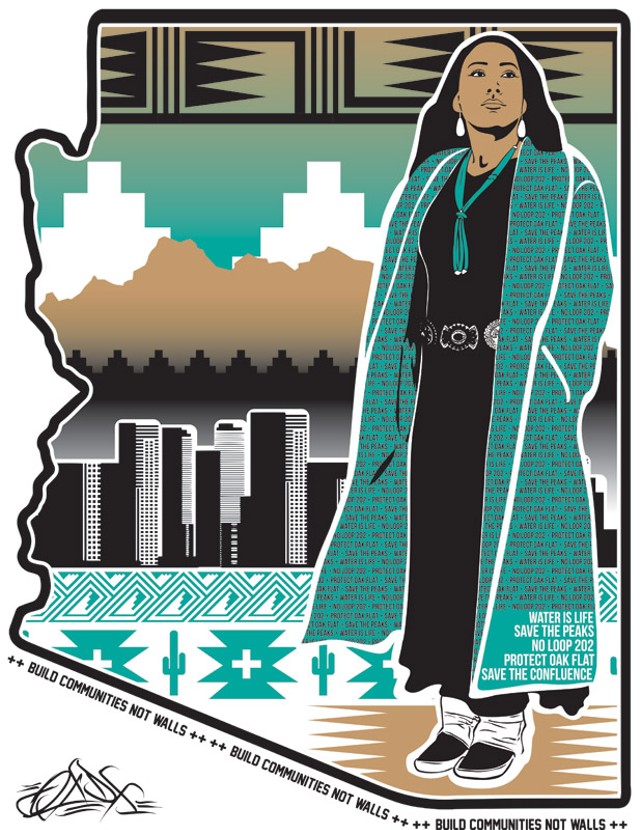

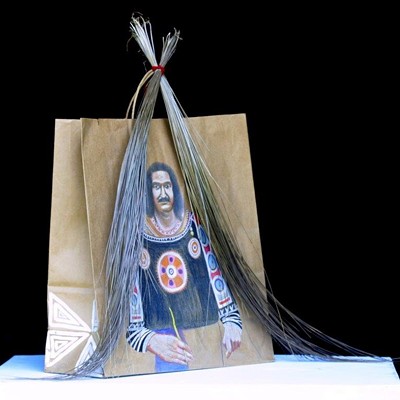

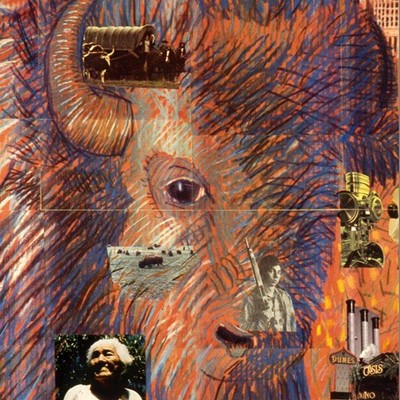

The show is sparse at the moment, but Jimerson and Kathy Farrell, MCC art professor and gallery director, plan to add more work to the walls throughout the run of the show. In addition to Jimerson's photography, the show includes art by Arizona-based artist and clothing designer Jared Yazzie (Navajo); Arizona-based doctor and artist Chip Thomas (aka jetsonorama), who has worked with the Navajo Nation since 1987; Seneca artist G. Peter Jemison; Seneca-Cayuga artist Tom Huff; and Oklahoma-based artist and model Erica Pretty Eagle Moore (Osage, Otoe-Missouria, Pawnee, Sac and Fox, and Prairie Band Potawatomi).

Jimerson met Yazzie last year when he came to Rochester for Native American Heritage Month. She says she's been a fan of his work for a while, and has followed his graphic design work and his clothing company, OXDX. Yazzie and Jimerson stayed in touch, and she asked him to be part of this show and put her in touch with other artists, which led to the connection with Thomas and Moore. And Jemison is her uncle and creates environmentally- and socially-conscious art, so he was a natural match.

"The show that I had imagined was very different," Jimerson says. "I wanted a bunch of posters from all over," but by the time she'd made contact with a range of artists, the timeline had about run out. So Jimerson and Farrell pivoted and refocused on the education aspect.

"It didn't get as big as we'd dreamed it would; we were thinking 20 or more people would partake," Farrell says, adding that she'd hoped the exhibit would be like the old mail-art shows, where the space would be filled floor-to-ceiling — which is still their goal by the end of the show's run.

"I always think of this as a teaching space," Farrell says. "Here at MCC, a lot of the students are so into their phones and everything but what's really going on, so I thought it was time for a wake-up call for a lot of them."

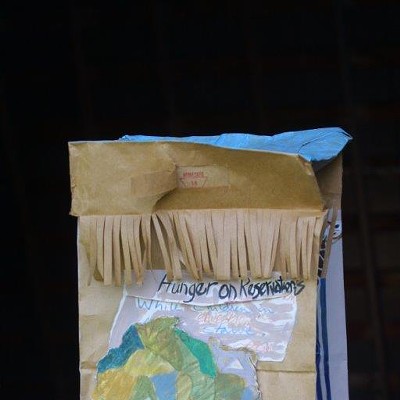

To fill out the space, they added a participation aspect. A table is set up with paper and markers so that students and visitors can make their own works on-site, and adhere them to the wall. The result is a modest collection of professional art and earnest doodles made in response to the shortsighted, environmentally damaging selfishness of various industries.

"We want to show people that there are ways of making change through artists' viewpoints," Farrell says.

Next to an ever-growing display of these drawings is a series of articles about the legal complexities of and violations to the DAPL protest that the gallery's student workers have posted. And at the gallery front desk there's a pile of free buttons: one reads "There is No Planet B" and the other is a cartoonish picture that basically translates to "Don't shit in the nest."

A series of videos are being projected on the space's back wall. Jimerson selected works that highlight environmental issues in Native America — particularly concerning the Sioux — which includes clips from "America Before Columbus" and "Dances With Wolves."

Jimerson wants the show to not only respond to the Standing Rock encampment, but also all of the different environmental issues going on around the nation. By way of example, she cites the Apache resistance to the Arizona Copper Mine in Oak Flat, and the resistance to the building of an observatory on Hawaii's Mauna Kea volcano, which is sacred to Native Hawaiians. In 2015, there was a copper mine spill in Colorado's Animus River that affected the Navajo people, Jimerson says.

"Standing Rock isn't something that is brand new," she says. "If you look at the history of the American Indian Movement, there's always been this overarching resistance against things happening concerning the environment. It's just that Standing Rock became this massive-scale resistance, and with social media involved, I think that's something that made it even bigger and brought this higher awareness to it. But it's something that's been going on for a long time."

The Haudenosaunee in particular, Peter Jemison says, have had numerous issues of different right-of-ways — powerlines, energy lines, and the NYS Thruway — that cross their territory and challenge the Canandaigua Treaty, which is the covenant between the Iroquois Confederacy and the United States Government.

"There are all of these continuing incursions into our territory that we've had to find ways to negotiate," he says. "Now we're still in a bit of a stalemate with the New York State thruway authority. It's ongoing — you have these outside agencies that feel as though they have a permanent right-of-ways, and don't acknowledge that they're going across sovereign territory. And getting them to work with the Seneca Nation is always a little bit of a challenge."

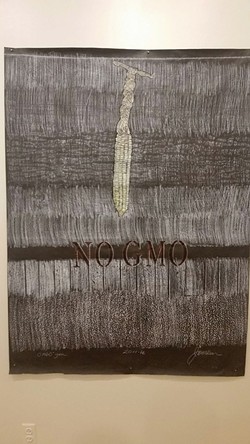

One of Jemison's works in the exhibit is a large, stark drawing of Iroquois White Corn with the phrase "No GMO" on it.

"All of us, Haudenosaunee and others, are very concerned that we do not lose control of our heirloom corn," he says. "And we have real concerns about the efforts of companies like Monsanto to get ahold of corn raised by Native people — one of the prime examples is Guatemala — and them saying, 'This isn't your corn, it's our corn. It's intermixed with our corn now, so it's our corn, and you have to come to us if you want corn seed.'"

There's a combination of wariness and a resolve for vigilance in his voice when he speaks about the tinkering with food. "We don't know what they've been doing as far as what they consider to be making it more disease-resistant, but that still has a very limited lifetime, as to how long it will be disease-resistant," he says. "And the unique thing about our corn is each of our kernels in unique. Corn is heirloom; it's very old, and each kernel is unique. We don't want anybody trying to take our corn and change it into something else."

Jimerson has lived in the Rochester area for about 20 years, but she grew up on the Cattaraugus Reservation. She first heard about the DAPL protest and occupation at the end of August last year and was following it, but at the time her life was too busy to allow a visit.

"Then things really kind of picked up in October, and a lot more people were moved to go and stand beside the people who were already there," she says. "When I started to hear about things that were happening to the people there — being attacked by dogs, being maced — it brought up a lot of things for me personally. We're looking at a history where our people have always been shot down, and it hit with a lot of Native people."

When Jimerson was working on her graduate degree, she learned about historical trauma and the toll that it takes on a person. "I felt myself having symptoms, feeling that past trauma, and having anxiousness, and I would read other people online were having these feelings," she says. "We're kind of in this era where we're trying to find our voices and speak out again" about the truth of what's happened to Native peoples historically and what's happening now.

Locally, the Canandaigua Treaty is commemorated every Veteran's Day. The keynote speaker at last fall's commemoration was Alex Hamer, who is a reporter for Indian Country Today Media Network. After Hamer showed the audience his pictures of what it was like behind the front lines at Standing Rock — how it was a family-centered place — Jimerson made the decision to travel to the camp.

"I don't really care too much to celebrate Thanksgiving; to me, it's not a celebration," she says. So she and Angel, who was then 18 years old, decided to go for three days. Her younger son wasn't able to accompany them.

"I decided to ask my children because this was a movement that began with the young people out at Standing Rock," she says.

They drove to North Dakota in one straight shot, and arrived late at night on Thanksgiving. Someone greeted them at the entrance and stated the rules: "No weapons, no drugs, no alcohol, and we're matriarchal."

"When we pulled in we could smell tobacco burning, and sage, and all of these smells that are familiar to us when we go into our ceremonies," she says. "Sometimes, because I live in an area where my ancestors lived — here in Victor, New York, or even the Rochester area, and part of my family came from a village in Canandaigua, so you know I kind of travel around this area where my ancestors lived their daily lives — I try to think about what it was like when we lived in villages. And at Standing Rock, I told them: 'This is probably the closest to that feeling that we'll ever have to the way our ancestors lived, because it was very community-driven. Everybody was just in that space together."

Jimerson and her son fed the water protectors with food from home, which included 13 gallons of cooked squash puree, harvested from her garden; 10 gallons of Iroquois White Corn puree; and more than 20 pounds of White Corn flour.

They stayed at the Haudenosaunee camp, and were surprised to find one of Jimerson's cousins and a few other people from her reservation were there, too. "I ran into people who I had not seen in years while I was at camp," she says.

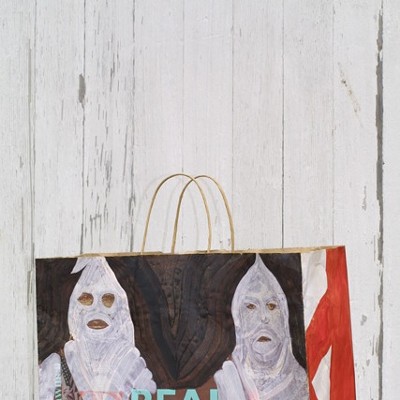

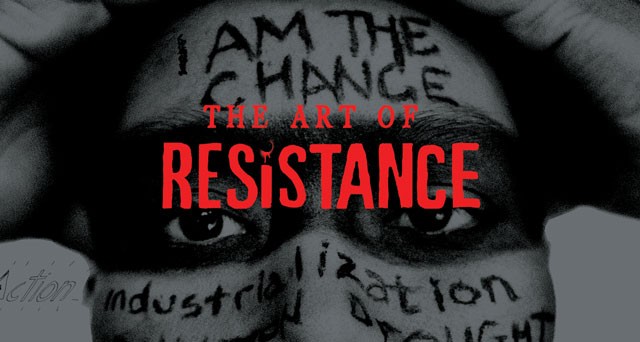

The cover photo to this CITY issue depicts Jimerson's son standing at the camp near a tall, many-signed post, which has since been collected by the Smithsonian. The post was originally a sign for the Haudenosaunee camp, but soon became a marker of how far people traveled to stand with Standing Rock. "People just kept writing on pieces of wood how far they came — people from Japan, people from Australia — and sometimes they'd write how many miles they came to be there," Jimerson says.

She estimates that when she was at Standing Rock there were as many as 10,000 people in attendance; this was just before the group of veterans were planning to come, which brought even more solidarity and greater numbers.

"They kind of got this thing stopped when the vets came through," Farrell says of the pipeline. "The vets became the human wall. And then we changed presidents, and now they're doing whatever they damned well please."

In the year since Jimerson attended the camp, there have been several DAPL oil spills, and in early November, South Dakota's Keystone pipeline leaked more than 200,000 gallons of oil.

"There's a sense of irony with that happening — I feel like there's just so much to be said about that," Jimerson says. "And I see this reflected in a lot of Indigenous issues. I think about the mascot issue. It's like, when are we going to be taken seriously?"

Jimerson is still reaching out to artists and hopes that more work will be added to the exhibit through the run of the show; artists can connect with her to submit work through email: [email protected].

EXTRA!

Art for sale: Through Mercer Gallery Jimerson is selling the posters as well as protest patches, and donating proceeds to Indigenous Environmental Network. "They're doing work not only covering environmental issues, but they went to the climate meeting in Paris," and are doing the work educating people about climate change and sustainable energies, she says.

Hudson Valley Earth First Action Camp: December 1-4. Workshops, education about the Valley Lateral Pipeline protest and more. [email protected] to RSVP or as questions. hudsonvalleyearthfirst.org.

Resources:

Indigenous Environmental Network: ienearth.org

International Indigenous Youth Council: indigenousyouth.org

Ganondagan & Seneca Art & Culture Center: ganondagan.org

Book: "No Reservation: New York Contemporary Native American Art Movement" by David Martine (available online)

Speaking of...

Latest in Art

More by Rebecca Rafferty

-

Beyond folklore

Apr 4, 2024 -

Partnership perks: Public Provisions @ Flour City Bread

Feb 24, 2024 -

Raison d’Art

Feb 19, 2024 - More »