James Brown occupies his familiar spot at the lunch counter of his namesake diner, James Brown’s Place.

[

{

"name": "500x250 Ad",

"insertPoint": "5",

"component": "15667920",

"parentWrapperClass": "",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

James Brown sat in his usual spot, on the last stool at the lunch counter in his namesake diner on Culver Road, thumbing through a stack of bills and reminiscing about his time in the restaurant game.

“The customers and the neighborhood, they made it fun,” Brown said. “But you can’t do it forever. I physically can’t do it anymore.”

He swung a beefy leg onto the open stool next to him and rubbed his swollen knee. It was flaring up again.

“It’s like being a pro athlete,” he went on. “You love the game, you love the smells, you love the fans, you love your teammates, but you just can’t play anymore.”

This would be his last year in the game. Brown, 68, said that he had arranged for James Brown’s Place, his undistinguished but somehow unforgettable greasy spoon, to be sold in October.

His diner has been an egalitarian enclave beloved in equal measure by power brokers and people living paycheck-to-paycheck, and from his perch on his stool, Brown has watched them and the Culver-Merchants neighborhood ebb and flow over his 22 years in business.

Now he watched a young man and young woman behind the counter prepare for a Friday morning breakfast rush. Their mother, Amanda Joyce, had agreed to buy the place and Brown was training them to take over.

Every now and then he hobbled to the grill on that bad knee to demonstrate how to slice a sausage link down the middle or chop a sizzling pile of spinach and tomato with a spatula.

“The best way to learn is to get on the line,” Brown said. “When I took over in ’98, my cook taught me to short order. I thought I had it down; then he went on vacation.”

To get up to speed, Joyce had been waitressing, cooking, greeting customers, and getting to know the place. Of course, as a longtime neighborhood resident she had known the restaurant for some time — and the value of its name.

“We looked at every kind of business you could think of to buy,” Joyce said. “I saw a diner and thought, ‘I don’t know.’ They don’t tell you the names of these things before you sign [a non-disclosure agreement]. Then I got the paperwork and I was like, ‘Oh my God, it’s James Brown’s Place. We’ve got to have it.’ That was it.”

Joyce and Brown expect the sale to close the first week of October. She said the name and recipes would remain the same for at least a year, possibly longer, and that Brown would still hang around.

“He’ll have a permanent seat right there,” Joyce said of his stool.

Brown had no experience as a restaurateur when he opened James Brown’s Place in March 1998.

He had spent the previous 22 years in sales, peddling everything from pharmaceuticals to costume jewelry and watch bands across a wide swath of the country. A native of Indianapolis whose career landed him in Columbus and Milwaukee for periods of time, Brown settled in Rochester when he took a job selling blue jeans for Levi Strauss & Company.

But he made, as he put it, “really, really, really good ribs,” and was flirting with the idea of starting a barbecue joint when John Savino, the former owner of Johnny’s Irish Pub — where Brown was something of a regular — told him that the diner next door to his bar was for sale.

The storefront had housed diners for 40 years, beginning with Jim’s Clock Luncheonette in the 1950s and most recently Mike’s Family Restaurant. With no spouse or children to support, Brown took a leap of faith and bought the place.

“I got tired of having money and time on my hands,” he quipped, then waited for the rim shot and the laugh with a comedian’s timing.

Brown, a squat and stocky man with an outsized personality, is quick like that. He has a vast portfolio of tried and tested one-liners he honed over a third of a lifetime on the road and another third schmoozing with diners.

An array of them are reserved just for people who ask him if he sings and dances like the Godfather of Soul with whom he shares his name. Brown, an affable man who’s otherwise quick to laugh, doesn’t find it funny.

“They all think they’re the first to say it,” Brown said. “You’re more like number 1,781.”

Over the years, he constructed a menu that blended classic American diner fare with innovative interlopers, like the carne adovado tacos and Cajun-influenced dishes inspired by his mother, who was from New Orleans.

A couple months before the pandemic forced him to close for a stretch, Brown introduced vegan versions of his traditional menu. He had gone vegan earlier and lost 80 pounds after his doctor warned him of the cruel irony that his eating from his own menu was killing him.

That James Brown’s Place was trading hands wasn’t being advertised, but there were signs that something was afoot. The most telltale among them was that nearly all of the New York Yankees paraphernalia that hung on the walls was gone.

The cream-colored walls were bare save for a couple of framed news articles featuring his restaurant that were published over the years. One of them was silver plated. Of all the memories Brown has of his place, the story behind that article was the most special to him.

Brown has stories. Lots of them. You just have to pull them out of him, which wasn’t difficult to do on a gray morning before he opened, when he was feeling sentimental about selling his place.

He figured he had told the story about the silver-plated article a thousand times and cried every time. He warned he would tear up again in just a few minutes; and he did, too.

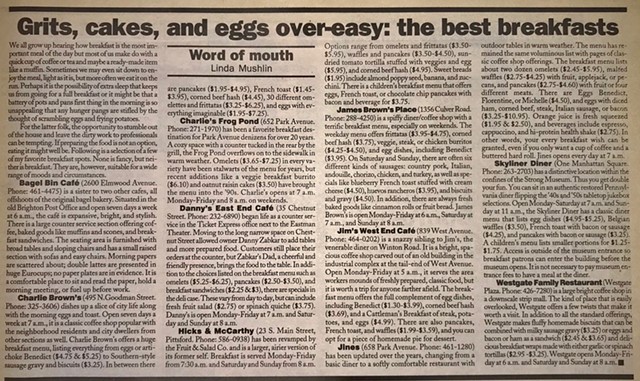

The article wasn’t even about James Brown’s Place. It was more of a roundup of restaurants printed in CITY Newspaper the week of Thanksgiving in 1998 under the headline, “Grits, cakes, and eggs over-easy: the best breakfasts,” and included a blurb on his place.

At the time, as Brown told it, he had been in the restaurant game for eight months and had worked every day of them with little to show for it. Business was slow and he was doubting himself.

“I began to wonder if I made the right decision because I’ve never failed at anything in my life,” Brown said, his eyes already starting to well up.

The newspaper was published on a Wednesday in those days, and that evening, after he closed up shop for what would be his first day off on Thanksgiving Day, he went to Johnny’s for a drink.

His spirits were buoyed when he saw his diner mentioned in the paper, but he still felt low and did through the holiday until he opened on the weekend.

“It was like they lit a bus outside; we were just packed, we were overwhelmed,” Brown said, choking back tears. “They had seen that article.”

His crew of three — himself, a waitress, and a busboy who doubled as a dishwasher — couldn’t keep up. It was a make-or-break moment for his place, and he didn’t have enough hands to make it.

Brown paused here in his retelling to shuffle around on his stool and compose himself, pursing his lips and swallowing hard.

“And then, the neighbors and the people in the restaurant started bussing tables, pouring coffee,” he said. “One guy got on the line with us. He said, ‘I’m not good, but I’ll try.’ I said, ‘If you can make toast we’ll be okay.’”

The waterworks were flowing now.

“That was when I felt like I was finally part of the neighborhood,” he said.

David Andreatta is CITY's editor. He can be reached at [email protected].

“The customers and the neighborhood, they made it fun,” Brown said. “But you can’t do it forever. I physically can’t do it anymore.”

He swung a beefy leg onto the open stool next to him and rubbed his swollen knee. It was flaring up again.

“It’s like being a pro athlete,” he went on. “You love the game, you love the smells, you love the fans, you love your teammates, but you just can’t play anymore.”

This would be his last year in the game. Brown, 68, said that he had arranged for James Brown’s Place, his undistinguished but somehow unforgettable greasy spoon, to be sold in October.

His diner has been an egalitarian enclave beloved in equal measure by power brokers and people living paycheck-to-paycheck, and from his perch on his stool, Brown has watched them and the Culver-Merchants neighborhood ebb and flow over his 22 years in business.

Now he watched a young man and young woman behind the counter prepare for a Friday morning breakfast rush. Their mother, Amanda Joyce, had agreed to buy the place and Brown was training them to take over.

Every now and then he hobbled to the grill on that bad knee to demonstrate how to slice a sausage link down the middle or chop a sizzling pile of spinach and tomato with a spatula.

“The best way to learn is to get on the line,” Brown said. “When I took over in ’98, my cook taught me to short order. I thought I had it down; then he went on vacation.”

To get up to speed, Joyce had been waitressing, cooking, greeting customers, and getting to know the place. Of course, as a longtime neighborhood resident she had known the restaurant for some time — and the value of its name.

“We looked at every kind of business you could think of to buy,” Joyce said. “I saw a diner and thought, ‘I don’t know.’ They don’t tell you the names of these things before you sign [a non-disclosure agreement]. Then I got the paperwork and I was like, ‘Oh my God, it’s James Brown’s Place. We’ve got to have it.’ That was it.”

Joyce and Brown expect the sale to close the first week of October. She said the name and recipes would remain the same for at least a year, possibly longer, and that Brown would still hang around.

“He’ll have a permanent seat right there,” Joyce said of his stool.

Brown had no experience as a restaurateur when he opened James Brown’s Place in March 1998.

He had spent the previous 22 years in sales, peddling everything from pharmaceuticals to costume jewelry and watch bands across a wide swath of the country. A native of Indianapolis whose career landed him in Columbus and Milwaukee for periods of time, Brown settled in Rochester when he took a job selling blue jeans for Levi Strauss & Company.

But he made, as he put it, “really, really, really good ribs,” and was flirting with the idea of starting a barbecue joint when John Savino, the former owner of Johnny’s Irish Pub — where Brown was something of a regular — told him that the diner next door to his bar was for sale.

The storefront had housed diners for 40 years, beginning with Jim’s Clock Luncheonette in the 1950s and most recently Mike’s Family Restaurant. With no spouse or children to support, Brown took a leap of faith and bought the place.

“I got tired of having money and time on my hands,” he quipped, then waited for the rim shot and the laugh with a comedian’s timing.

Brown, a squat and stocky man with an outsized personality, is quick like that. He has a vast portfolio of tried and tested one-liners he honed over a third of a lifetime on the road and another third schmoozing with diners.

An array of them are reserved just for people who ask him if he sings and dances like the Godfather of Soul with whom he shares his name. Brown, an affable man who’s otherwise quick to laugh, doesn’t find it funny.

“They all think they’re the first to say it,” Brown said. “You’re more like number 1,781.”

Over the years, he constructed a menu that blended classic American diner fare with innovative interlopers, like the carne adovado tacos and Cajun-influenced dishes inspired by his mother, who was from New Orleans.

A couple months before the pandemic forced him to close for a stretch, Brown introduced vegan versions of his traditional menu. He had gone vegan earlier and lost 80 pounds after his doctor warned him of the cruel irony that his eating from his own menu was killing him.

That James Brown’s Place was trading hands wasn’t being advertised, but there were signs that something was afoot. The most telltale among them was that nearly all of the New York Yankees paraphernalia that hung on the walls was gone.

The cream-colored walls were bare save for a couple of framed news articles featuring his restaurant that were published over the years. One of them was silver plated. Of all the memories Brown has of his place, the story behind that article was the most special to him.

Brown has stories. Lots of them. You just have to pull them out of him, which wasn’t difficult to do on a gray morning before he opened, when he was feeling sentimental about selling his place.

He figured he had told the story about the silver-plated article a thousand times and cried every time. He warned he would tear up again in just a few minutes; and he did, too.

The article wasn’t even about James Brown’s Place. It was more of a roundup of restaurants printed in CITY Newspaper the week of Thanksgiving in 1998 under the headline, “Grits, cakes, and eggs over-easy: the best breakfasts,” and included a blurb on his place.

At the time, as Brown told it, he had been in the restaurant game for eight months and had worked every day of them with little to show for it. Business was slow and he was doubting himself.

“I began to wonder if I made the right decision because I’ve never failed at anything in my life,” Brown said, his eyes already starting to well up.

The newspaper was published on a Wednesday in those days, and that evening, after he closed up shop for what would be his first day off on Thanksgiving Day, he went to Johnny’s for a drink.

His spirits were buoyed when he saw his diner mentioned in the paper, but he still felt low and did through the holiday until he opened on the weekend.

“It was like they lit a bus outside; we were just packed, we were overwhelmed,” Brown said, choking back tears. “They had seen that article.”

His crew of three — himself, a waitress, and a busboy who doubled as a dishwasher — couldn’t keep up. It was a make-or-break moment for his place, and he didn’t have enough hands to make it.

Brown paused here in his retelling to shuffle around on his stool and compose himself, pursing his lips and swallowing hard.

“And then, the neighbors and the people in the restaurant started bussing tables, pouring coffee,” he said. “One guy got on the line with us. He said, ‘I’m not good, but I’ll try.’ I said, ‘If you can make toast we’ll be okay.’”

The waterworks were flowing now.

“That was when I felt like I was finally part of the neighborhood,” he said.

David Andreatta is CITY's editor. He can be reached at [email protected].