[

{

"name": "500x250 Ad",

"insertPoint": "5",

"component": "15667920",

"parentWrapperClass": "",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

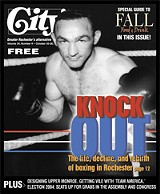

It was a cool July night this past summer as Charles "The Natural" Murray faced his final opponent, gloves up, eyes intent. It wanted to rain. The sky threatened to break as 5,000 boxing fans piled into Frontier Field to see 18 fighters square off in nine pairings, including Murray's swan song.

They call it the sweet science. It requires skill, strength, and guts. Most people involved in the sport laud the boxers' heart, drive, tenacity, and respect --- all of which are undeniable. Yet there still lurks an underlying brutality, and some are intoxicated by the sport's noirish violence. Whatever the attraction, there is one constant fundamental: an intense passion. A passion that is apparent to both the casual observer and the fan that jumps at every opportunity to cheer ringside.

The fight at Frontier Field was right out of a movie, timeless. You could almost see it in black and white. The fighters duked it out in a ring erected over home plate, beneath the haze of the hot infield lights. Shouts cut the air. "Oohs" and "aahs" accompanied each landed blow or deft move. An old man with an unlit, half-chewed cigar watched intently, kept score, and imparted wisdom.

"Stick and move, baby," he yelled. "Stick and move."

A young woman near the ring, brought to her high-heeled feet each time the action got hot, clapped furiously.

"Break his face," she hollered.

It's in this sport, and its often-debated juxtaposition of art and brutality, that The Flower City has earned a proud history over the past 150 years. We've had our share of fight firsts, historic events, and champs. Rochester has raised and hosted more than a few contenders on their way to fame and champions in their prime.

Rochester was on the map during the sport's pre-war, wartime, and well into its post-war heyday, when boxing was perhaps second only to baseball as America's favorite sport.

"Rochester was one of the Meccas of boxing," says Rochester Boxing Hall of Fame founder and president, Tony Liccione. "Right up there with Cleveland and Buffalo. You had a gym on every corner." Liccione and Hall of Fame co-founder and boxing historian Larry Allen can't seem to get the names, stats, and facts out fast enough. Their faces light up enthusiastically as it all pours out.

"Rochester boxing history goes back to 1860," Liccione says. "We are fortunate when we look at the history books of boxing, you see that bare-knuckle championship bouts took place here in Rochester with John Sullivan, Gentleman Jim Corbett --- some of the great fighters of that era."

Worldwide news was made August 11, 1916 when Rochester heavyweights Charley Gouse and Sam Nolan knocked each other out at the end of the sixth round.

On December 13, 1924, Rochester's Mike Conroy won the South and Central American Heavyweight title from Antolin Fierro by knocking him out in the fifth round in Havana, Cuba.

In Rochester's neighborhoods, boxing was and still is more than a pastime; it's also a ticket for kids looking for a way out.

"The Italians, the Irish, the Germans tried to find a way out," says Liccione. "It's all changed of course. The Blacks and Hispanics are where we were 50 to 60 years ago."

"It was their ticket out of the ghetto," Allen says.

Allen first fell in love with boxing when his parents took him to the Dixie Theatre on Portland Avenue, where highlights of the James Braddock-Max Baer fight flickered on the screen before the feature.

"Of course in those days everything was black and white," he says. "Harry Balough --- one of the world-renowned announcers --- was wearing a tuxedo, very elegant. And they bring down the microphone, and I'm five years old, my heart started pounding, and I said, 'This is fantastic.' It was like being transported to another world... That was the beginning of my love."

Allen fought in Aquinas High School's boxing program all four years. Known as "The Loquacious Warrior," he successfully fought amateur after graduation and even toyed with the idea of turning pro.

Liccione and Allen go on and on about local historic boxing figures like Mike Dempsey, Joey Manuel, Frankie Verna, Sr., Nello Nucelli, Ossie "The Jewish Buzz Saw" Sussman, and Frank Powderly. They talk about events like the Kodak smoker bouts in the '30s, fights at The Elks Club, and the Tournament of Champions in 1940.

"The great Sugar Ray Robinson, considered by many, pound for pound, the greatest fighter of all time, fought his last amateur bout here in Rochester before a crowd of 10,000 at Red Wing Stadium on Norton Street," says Liccione.

"Against Tommy Moyer," adds Allen, "who almost beat him."

And then there's Carmen Basilio.

"On his way to fame, Carmen Basilio engaged in three bouts here," says Liccione. "Who knew that he would become one of the greatest, most courageous, most popular boxing figures of all time?"

"My goal from when I was a little boy was to be a world champion, to be a fighter," Basilio says from the trophy room in his Irondequoit home. The room is covered floor to ceiling with portraits, trophies, boxing gloves, and magazine clippings, including the September 16, 1957 issue of Sports Illustrated with a young Basilio on the cover. "My father bought us boxing gloves for my brother and I. He'd make us box all the time. If we'd get in an argument he'd say, 'OK, box.'"

Basilio boxed his way onto the Canastota High School boxing team.

"If you want to know the truth," he says, "if it wasn't for that boxing team, I probably would have never went to high school."

When Canastota dropped its boxing program, Basilio dropped out and joined the Marines. He returned from his hitch with Uncle Sam to work on his father's onion farm and pick up the occasional 10 or 15 bucks fighting amateur.

"Everybody used to say to me, 'What are you gonna do? You gonna keep on fighting?' And I said, 'Yeah. I'm gonna be champion of the world.' No one could change my mind. I'm glad they talked to me that way, 'cause all it did was inspire me to work harder, to prove them wrong, make them eat their words."

After the 1947 harvest, Basilio couldn't find a job. So he turned pro.

"I had my first professional fight in November of 1947 in Binghamton," he says. "I won by a TKO in the second round."

His big chance came on September 23, 1957 when he faced Sugar Ray Robinson in Yankee Stadium for the Middleweight Championship title in front of 38,000 fight fans. Millions more caught the fight on TV. Robinson was favored to win, but Basilio didn't buy into the hype.

"Bullshit," he says. "He was an arrogant fool. You couldn't talk to him, he was such a big shot. There was no love between him and I. As a matter of fact, he hated me, said he's gonna knock me out, he's gonna do this to me, do that. He didn't scare me. I said, 'Let him do all the talking he wants and we'll prove everything the night of the fight.'"

Basilio won by a decision after 15 rounds.

On April 22, 1961 Carmen Basilio fought his last fight in Boston and retired with a 56-16-7 record. He then taught physical education at Lemoyne College for 30 years.

And though his rec room is a shrine to boxing, Basilio, now 77, doesn't really follow the sport anymore.

"Nobody impresses me right now," he says.

The last fighter to impress him?

"My wife."

It wasn't long after Basilio hung up his gloves, that boxing, according to some aficionados, went into a decline. Showbiz sleaze, corruption, and the almighty dollar stepped in.

Liccione, and others like him, long for boxing's golden age.

"Today's boxing, I don't get into it much," he says. "I don't enjoy watching a fighter come in with pink shoes, tassels on his braids. However, once in a while you get Arturo Gottis, Mickey Wards, and Bernard Hopkinses that are throwbacks to the old days.

"What changed it," says Liccione, "was promoters like Don King and Bob Arum after the Basilio years, the '50s and the '60s.

"You got cable, HBO, and it began a really mega-promotion with sponsors and boxers. Millions of dollars were involved and it just kinda killed the small venue," he says.

"Everybody was looking for the quick buck," says Allen. "I think with a lot of the champions, it's who you know. The ratings are fixed --- they're purchased."

And more and more a general disdain for the sport's brutality began to emerge. Boxing's vicious side started to get played up.

"There was a lot of 'this sport's brutal' and this and that," says Montgomery Boxing Club's Ron Resnick. "I think a lot of bleeding hearts took away from it."

That fear of the sport's violence still crops up. Six years ago, Aquinas High School's Mission Bouts --- the annual fights that are part of the school's boxing program --- were almost eighty-sixed. In the wake of Columbine, people were looking for anything that might lead to violence in kids. And some educators and doctors fixed their eyes on boxing.

A panel, including a clinical psychologist, a dentist, a priest, and a Supreme Court judge, was put together at Aquinas.

"It ended up elevating the program even higher," says Dominick Arioli, who has coached Aquinas's boxing program for the past 25 years. Even the psychologist came around.

"In the beginning, she was against it," he says. "But, she found out that kids that went to our program were less violent. She recommended that all kids go through the program."

In fact, two former Mission Bout participants, now dentists themselves, make all the mouth guards for the kids.

"It's really not that dangerous as compared to other sports," says Pete Fornarola, an Aquinas senior and boxer. "At Aquinas there are more injuries in more conventional sports than there are in boxing."

But Arioli does acknowledge that dangers exist at the pro level, and that they can cause concern.

"A lot of people see the aftereffects," he says. "These guys have been doing it for years. Some of them have taken too many punches. I mean, they're doing it day in and day out. It's gonna have its toll."

Some of these damaged fighters have simply fought past their shelf life.

"A boxer really has five to seven good years in his prime," says Liccione.

Recent regulations have led to improvements. Resnick commends the New York State Athletic Commission's efforts.

"If you watch boxing now, they're stopping the fight a lot quicker than they did in the '20s and '30s," he says. "Back then, there were no 12 rounds. They just kept fighting until somebody quit --- last man standing."

The integrity and drive of the small venue and the heart of real boxing is still found in places like the Montgomery Boxing Club on Lyell Avenue. Resnick has run the gym for the past five years and serves as an amateur and pro trainer and local promoter.

Resnick was an amateur boxer and trainer, and took over the gym from its former owner when the only other option was closing down. The fight promotion came later.

"Nobody else was doing it properly in Rochester," he says. "I had a couple of my boxers that were ready to turn professional. I'd seen a lot of local boxers that should have turned professional that didn't have the people behind them, they didn't have a place to box. They didn't have the right people to put them in the ring and put the right fights together."

Resnick promoted the July 28 fight at Frontier Field. It was the first outdoor boxing event in Rochester since the Ross Vergo-Tony Pellone fight at Red Wing Stadium in 1949.

The program at Aquinas is another constant in the Rochester boxing scene. It's a holdover from boxing's heyday, when it was considered a gentlemanly way to settle disputes.

"Seventy-three years ago, two students got into a fight," says Aquinas coach Arioli. "And the priests at the time said, 'Let's settle this like gentlemen. We'll go into the gym and put boxing gloves on.'"

One of the priests got the idea to charge admission and give the proceeds to the Aquinas mission. "That's what set it off," says Arioli. "Two kids with a beef."

Aquinas's is virtually the only high-school boxing program left in the country.

"Last year, I had 90 kids sign up," Arioli says. "And we had 75 kids that actually went through the program." The Bouts, held each March, consistently sell out and raise between $4,000 and $5,000.

"Mr. Arioli is a great guy," says Pete Fornarola. "Everything that he says you can learn something from --- not just about boxing, but about dedication and self confidence."

Fornarola plans on pursuing boxing "however far I can go" and is looking at schools like Pennsylvania State and University at Buffalo that have boxing programs.

Other kids, like Ron Resnick's 16-year-old daughter, Dena, have even loftier goals.

"I plan to go to the Olympics," she says. "But right now they don't have women's boxing in the Olympics. Hopefully it changes. I'm hoping, I wish for it. That's the dream."

Her drive is admirable. She's an instrumental major at School Of The Arts. She swims, plays lacrosse, soccer, volleyball, basketball, and "even cheerleading," she adds with an embarrassed laugh.

"I'm basically a tomboy," Dena says. "I can do anything a guy can do, probably better." But that doesn't always work in her favor.

"It's hard to find girls my age," she says. "So I've been sparring guys ever since I was little. Every guy's got a fear about being beat up by a girl, but it's a motivation for me, definitely."

Dena helps out with the beginner program at her dad's gym between her busy schedule and own workout.

"It definitely keeps me out of trouble," she says. "I'm a good girl." A good girl who could knock your block off.

Amidst the youth at the Montgomery Boxing Club gym is Robert Johnson, a boxing coach for "about 35 to 40 years" and a highly revered figure in local boxing. He got into the sport as a child when he didn't measure up for basketball. And over the years he has worked with local contenders like Pablo de Jesus, Robert Dixon, Frank Mittigan, Willie Monroe, Charles Murray, and Robert "Pushup" Frazier. New fighters still seek out his expertise.

"I don't say yes right away, anyhow," he says. "I have to see that he really wants to do it. Because it's not a sport you just come in and do it half-ass. You can get hurt in this sport. So you have to have really made up your mind that you want to do this. Show me you want to do this. Once you get in the ring and put those gloves on in a sparring session with a guy that's already boxing, that tells it, that tells 'em right away. You gotta like to get hit."

But that's only part of it, according to Johnson.

"A boxer uses his brains as well as his hands as well as his legs," he says. "A puncher goes into the ring with the mentality of just brutalizing the other guy. And that takes away from the thinking."

Recently retired champ and Johnson protégé Charles "The Natural" Murray fought around neighborhood streets and found himself attracted to boxing's "artistic aspect."

"I just happened to be good at it," he says.

Murray turned pro when he was 19, almost making it onto the Olympic boxing team.

"After the Olympic trials, a couple people came to ask me about turning pro and joining the organization," he says. "And I went with it."

Murray boxed pro as a junior welterweight and won the world title in 1993. He retired at age 35.

"It just stopped being fun to me," he says. "The business aspect was getting me down a little bit. And it was hard for me to excel when I stopped having fun."

The fun returned for Murray about three years ago when he took over The Avenue D Recreation Center's Youth Boxing Program from Coach Johnson.

"It's a thrill for me to see them perform something that I taught them," he says. "I like the kids a lot. I think they look at me as a sports figure, but I'm close to them."

Roughly 30 kids --- age five and up --- tear around the gym but snap to attention when Murray speaks. There are running drills, sprints, pushups, and sparring. Little boys with gloves bigger than their heads meet in brief mini-bouts within a circle of their peers. Their eyes burn fiercely as they execute Murray's on-site instructions amidst the cheers. Some swing wildly, wind-milling around their opponent, other hunker down and deliver surprisingly well-executed jabs and uppercuts. All seem to be having a great time.

"I'm a single mom so I feel this is a good place for him to be," says five-year-old Jahki's mother, Avrish Lewis. "He's young, he's gonna have good motivation skills, and he's being around males."

She's not really worried about him getting hurt.

"If he gets a scratch or a bruise, he'll learn how to dust it off," she says. "That'll help him become a man in the future, because things like that are going to happen in life. You get boo boos all the time."

At the heart of the instruction are lessons these youngsters will carry with them for life, boxing or not.

"I teach them about giving their all into everything they do," Murray says. "I emphasize school to the kids and never looking at boxing as a profession but as a recreation. I give them a lot of things about respecting each other, respecting their selves."

Maybe someday one of these kids will join the ranks of current hometown up-and-comers like Robert "Pushup" Frazier, Rodney Jones, and Jonathan Tubbs, who is "the hot kid right now," says Resnick.

Resnick will promote the next big fight night in November at the Riverside Convention Center. "I think we've got a good fan base," he says. "We're starting to build on it."

At the heart of these fans and the heart of the fighters beats a passion, a drive. Just listen to its future.

"Boxing's about 85 percent heart, 15 percent skill," says Dena Resnick. "I've got heart. I've got the heart for boxing. You've gotta have heart."

The next Boxing at the ROC is Thursday, November 4, at the Riverside Convention Center, 123 East Main Street, 7:30 p.m. Tickets: $20-$75. Info: 254-3280. For more information: www.rochesterboxing.com.

Speaking of...

-

Reader feedback 11.17.04

Nov 17, 2004 - More »