[

{

"name": "500x250 Ad",

"insertPoint": "5",

"component": "15667920",

"parentWrapperClass": "",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

No two artistic paths are alike. On living a creative life, "The Hero's Journey" author Joseph Campbell said: "If you can see your path laid out in front of you step by step, you know it's not your path." But as you're carving your path, you'd better be carrying a machete, he said, referring to the messy weed-whacking required to create your own trail.

Following your creative bliss is hard work, and for most artists this labor is overtime, done between and after hours spent at day jobs where they earn the means to live. Success often emerges from the precarious balance of dedicating lonely hours to their craft and finding crucial social connections within a creative scene.

Each year for our Emerging Artists series, CITY spotlights four young artists who are creating engaging work but are still in the early years of their artistic careers. Our 2018 selections — photographer Will Cornfield, painter G. E. DeGroat, assemblage artist and vintage pinball machine restorer Ashley Ludwig, and experimental film artist Alexandria Mockbee — are each creating their own paths, taking chances and often unexpected opportunities to find their way forward.

Will Cornfield: Photography | willcornfield.com; @willcornfield

It's not common for a 24-year-old who is not a celebrity to have tens of thousands of followers on Instagram. Will Cornfield's current number is more than 32,000 people. They follow him for his dreamy, fashion-inspired digital portraits of beautiful youths striking poses in wide open fields or in abandoned industrial settings.

Cornfield's talent occasionally takes him on the road; he recently returned from shooting at the Lynchstock Music Festival in Virginia, where he was hired by organizers to document the sights. He also takes client-based formal portraits for some companies in Rochester, and works as a bartender at Radio Social.

The influence fashion has had on Cornfield's work is clear: Each of his diverse set of models looks slightly intimidatingly cool and self-possessed, and their stances deliberately showcase their threads. They make moody, direct eye contact with the camera, or they stare into the middle distance, absorbed in some private thought. Occasionally there's a shot capturing an unguarded moment of effervescent grinning.

Like many portrait photographers, Cornfield loves capturing subjects in the "golden hour" right as the summer sun is setting, or taking advantage of the scattered light from an overcast sky. The gloominess makes every hue in the image pop like crazy. He's a true ace at getting his angles and lighting just so, capturing sun-kissed cheekbones and making use of shadows that partly obscure a subject. And he takes advantage of the fact that we actually have four seasons here, shooting outside throughout the year, in humidity and icy wind alike.

Cornfield chooses his subjects based on simply spotting someone who he thinks looks interesting, and he'll approach strangers to ask if he can photograph them — "sometimes at a café, sometimes when I have a little more courage after a drink at a bar," he says with a laugh. His supremely chilled-out personality makes him an easy person to talk and work with, and he's also learned from being on the other side of a camera when he's modeled for student photographer friends.

He has a hand in styling the models and directing them throughout the shoots, and will go thrifting for clothing with his models, but he'll occasionally work with a makeup artist or stylist to achieve a specific look.

There's also a cinematic feel to Cornfield's images, which he says is inspired by single frames in films that have caught his attention and stick with him — most recently the 2017 film "A Ghost Story." "The final goal, the goal through editing, is to make it look like it's a part of a movie," he says of his work.

Cornfield's appreciation for photography began early: He took a photography class in grade school, and would frequently capture imagery with disposable cameras and borrow his mom's Cybershot camera. But it was the social media platform that secured his interest in pursuing photography seriously. Instagram had just emerged as a platform for sharing images when he was in high school.

Cornfield, his cousin, and friends would take photographs using their iPhones while out on rambles in their hometown of Corning. They'd snap and share images of each other and interesting bits of rural nature.

Cornfield says his number of Instagram followers began to balloon while he was still in high school, and he was able to connect with photographers all over the country who taught him things. "All because of this app," he says.

He realized he needed to focus on creating better and better content. Freshman year he saved up money and bought a decent starter digital camera from a friend, but says he still shot mostly with his iPhone while he learned to use the camera.

His method of creating work is pretty on-the-fly, even in the cases when he's spent weeks thinking about and planning out a shoot, mood boards be damned. "My general process is: Waking up in the morning, seeing that it's a nice day outside, knowing that I want to go shoot, and texting five people to see who's available," he says. "A lot of the time, those are the best shoots."

Cornfield meets up with whoever gets back to him, and puts some thought into finding the right location to match the weather and whatever clothing his model is planning to wear. "It could be just one yellow wall I've seen that's part of a larger building," he says. "And I just want to shoot the yellow wall, so that's the location."

This easy-going approach comes from his habit of doing on-the-go photography using his phone.

"Shooting with just an iPhone taught me so much," he says. "You don't have control over anything. Whatever is there in the moment is what you get. So you have to control your angle, you have to pay attention to the lighting: where it is, how to use it."

Cornfield's primary camera is a Canon 5D Mark IV, and he carries only two lenses: a 24-70 lens that he uses on jobs, and the one he uses for his art photography is a Sigma 35mm. "It translates to how I used to use my iPhone, because it doesn't have a zoom on it, so you have to kind of move your feet to get the shot," he says, adding that he spends a lot of time lying on the ground to capture the right angle. "I'm pretty much on the ground for like half the shoot."

While he does have some lighting equipment, most of his images are shot in natural light. Cornfield says this is another relic from learning photography on his phone, but he also just prefers the look of natural light.

Cornfield has the audience, but says he'd like to expand beyond sharing his work on Instagram and his website. He's like to get into editorial fashion photography, but says he's waiting for the right project to come along. And he has a project in the works to create physical versions of his images.

"I've been really picky about it, working on it for a while," he says. "And I want to just finally get it out there. But in order for me to do that, I just need to love it a lot, so my goal is to start creating work that I love so much that I want to print out."

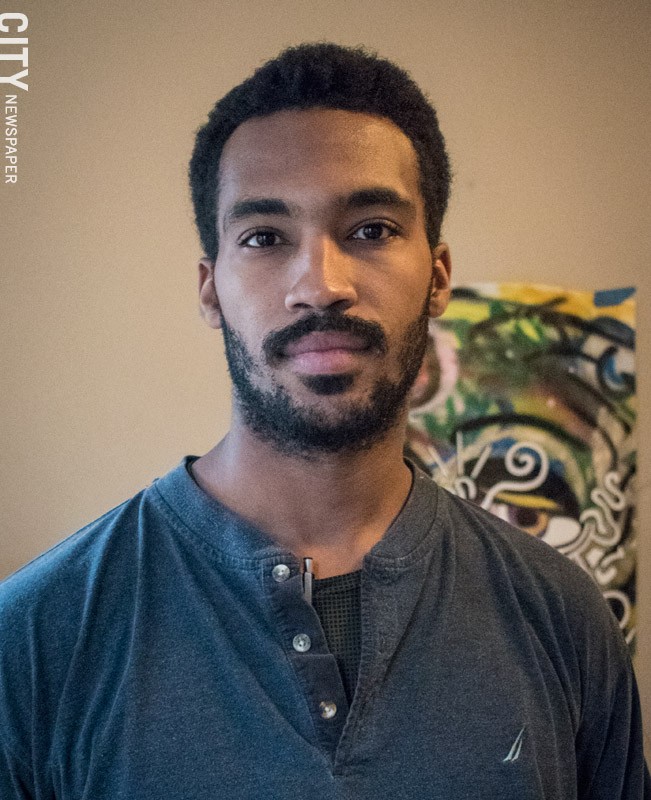

G.E. DeGroat: Painting | @g.degroat

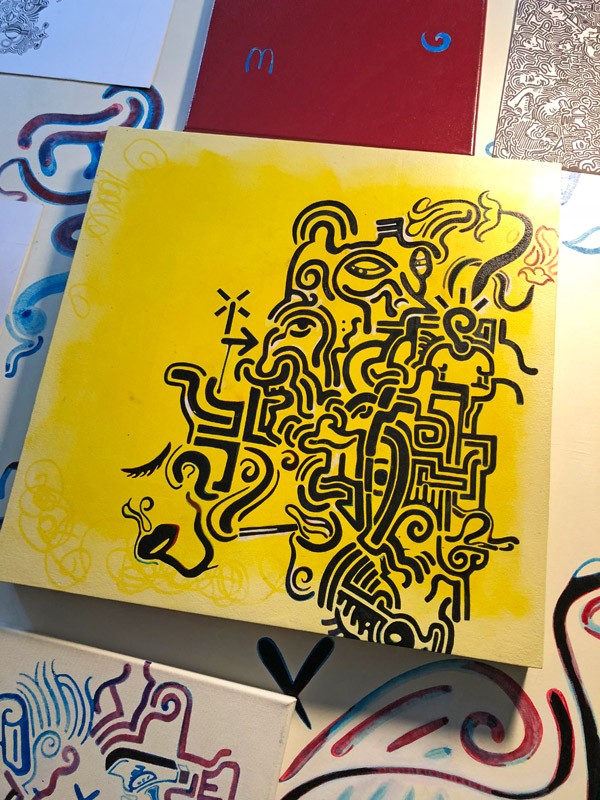

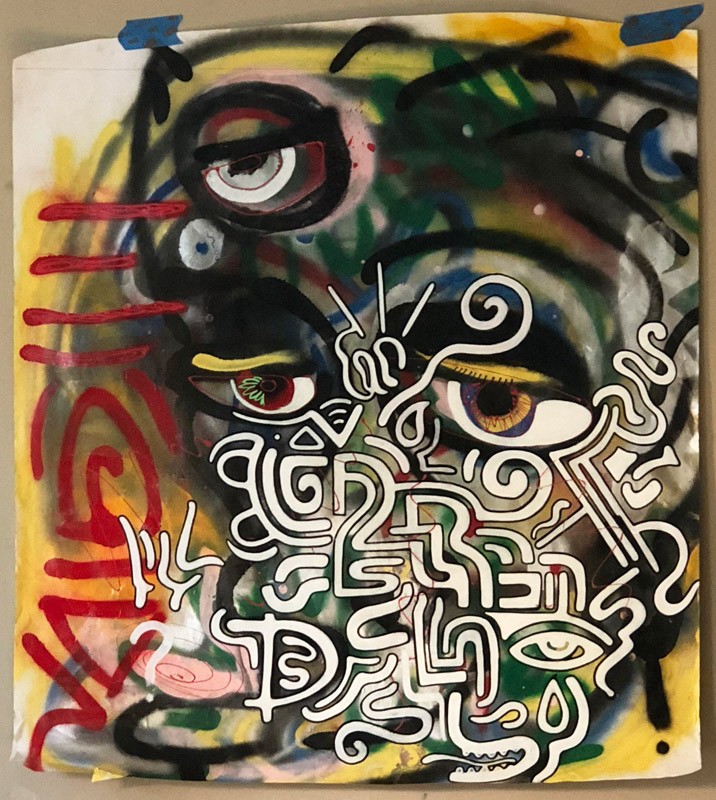

An array of works in progress and finished paintings and collages cover the walls and tables of G.E. DeGroat's dining room studio. Images of his two cats — one sweet, one temperamental — have made it into some of his work. Everything is fair game in his art, which includes a metamorphic tangle of thick-lined, maze-like patterns, snippets of language and symbolism, and bits of human forms.

"Every painting starts out freeform," DeGroat says. "I'm just trying to unpack my experience as a sentient being. This is all that I'm taking in."

His current set of in-progress paintings deal heavily with language, symbolism, and iconography. "All of my paintings start out pretty random," he says, "but I do impart some specific motifs, like deconstructing ASL. There's a couple of hand signs I've been deconstructing in there, like 'I love you' and the sign for 'W.'"

DeGroat was hired by Bar Bantam to design and paint the bold-lined patterns and motifs that adorn the walls and menus. His background is in graphic design, which he studied at the Art Institute in New York City before dropping out and working as a freelance designer and model, among other odd jobs.

"When I left school and I was freelancing, one of my favorite things to do was to come up with a logo for people. And I'd do pages of drawings that would morph into each other," he says. "If I'm drawing a face, the face is also a body, and the body might be a bottle, or a cat."

The 28-year-old artist says he's fascinated with individualism, and with language as the connective force between individuals.

"Everyone is their own universe. Even Goose might be his own universe," he says of the friendlier of his two cats.

DeGroat says part of his work is about sitting with and appreciating the bittersweet moments of life and of ourselves. "I've dealt with depression and mental illness in my family, and I personally have experienced depression," he says. "But at the same time, there's moments of beauty in that depression, and that's totally the ego talking. It's like, this is a beautiful moment but I feel like crap; I'm questioning everything around me; I'm questioning my own existence; why am I here and whatnot.

"I really like the challenge of taking what you have and then making something from it," he says, "whether it's me as a 15-year-old downloading software to make music, or me being depressed and finding beauty in that."

DeGroat says one of his earliest memories is of his mother sitting him and his sister down before bed to sketch them. "I guess that's what planted the idea of drawing in my head," he says, adding that he's been drawing since he could hold a pen. "I decided at a very young age that I wanted to spend most of my time creating for myself."

He was born on Staten Island, but grew up in Newport News, Virginia. "As soon as I graduated from high school I had to get out of there, because I was very close to falling into a street scene," he says.

After high school he went to live with his father in New York City where he dabbled in hip hop, rapping for about a year before enrolling in school.

Reflecting on his time in design school, he says: "I think I had a really good hand back then, but I realized a lot of people have a really good hand."

But DeGroat's proximity to the New York art scene was influential. He says seeing street artist Shepard Fairey's work up close at Jeffrey Deitch Gallery was particularly pivotal. "I was a fan as a designer," he says, "but was stunned by the painterly, tactile quality of the layered stencils."

DeGroat's love of art history shows in up his work in references to works by old masters, such as Michelangelo, Vermeer, and Rubens. "I literally steal from them," he says. "I've got a ton of art books of my favorites."

And specifically, learning about the Surrealists has been influential, he says: "I've got this constant internal dialogue going on, and Surrealism kind of embodies that metaphysical energy or survey. I would say the paintings that I'm getting ready to show are not just surveys of the physical world, but they're also metaphysical world surveys."

DeGroat says he's hugely inspired by renowned performance artist Marina Abramovic. "She lives art," he says. "She's really unpacking this thing, this human experience thing, like nobody else is. I paint, I'm not a performance artist, but I feel like it's all the same thing. Not technically of course, but what she's doing artistically inspires me the most. Empathy is huge for me, just relating to other humans."

DeGroat is relatively new to Rochester, having moved here from Virginia in the summer of 2017, initially intending to visit friends he'd met in Brooklyn. He works as a support staff member at Cure in the Public Market, which he says is more than a job he's taken to support creative endeavors. "I dig the background operations of support staff, and after Rochester I'd like to go somewhere else, maybe France," he says. "I entertain the thought of being a maitre d' at a restaurant or something like that."

And working in cafe and bar culture is a common way that artists use to get out of their isolating work modes and remain social. "Creating something from nothing is exhausting," he says. "So you spend a certain amount of time working, and then you need to go out and be social. I have this habit of working for hours and researching during the daylight, then socializing at night. I think the key to everything is momentum."

DeGroat's exhibit, "Free Association," opens at The Yards Collaborative Art Space on November 16.

Ashley Ludwig: Mixed media and pinball restoration | @ludwigsynopsis

It's no secret that most artists have some sort of day gig that sustains them while they pursue their craft, usually afterhours or on weekends. What's less common is when the 9-to-5 job is itself an art career. On her own time, Rochester native Ashley Ludwig creates mixed media works that she says are inspired by the human experience. But her bread and butter comes from working as a restorer of vintage pinball machines at Pinball Alley in Henrietta.

Getting into that line of work was the result of her savvy approach to staying connected to art through paying gigs. She actively looked for and was open to taking unusual, chance opportunities. In this case, the breadcrumb trail was an ad on Craigslist.

"Almost three years ago I was suffering through a quarter-life crisis, which I believe many of us do," she says. "I graduated from college, had a degree in hand, and was applying to jobs all over the country with no luck."

To keep her portfolio current and to stay engaged with the arts community, she volunteered and joined creative projects (she's been an active volunteer for WALL\THERAPY for years) and occasionally found random creative jobs on Craigslist, like sign painting for restaurants.

Ludwig stumbled on an ad titled "artist needed to restore pinball machines" and initially laughed, assuming it was a scam "because it sounded too good to be true," she says. "Several months later, I ended up responding to the ad because I figured I had nothing to lose."

In the beginning, once a week Ludwig took her artistic skillset to work on a pinball machine called "Road Kings." Over time she realized she could actually carve a name for herself in this niche field, and took the risk of leaving her secure and steady job to learn how to be a full-time restoration artist working on pinball machines.

"The cabinet and playfield are constructed from wood and are either originally stenciled or decaled with the artwork," she says. "I do a lot of woodworking and prep on surfaces: Repairing surface scratches and dented or broken corners or edges, basically any damage done to the wood by filling and sanding."

After the surfaces are restored comes the painting. Ludwig works to match the original colors and styles, then finishes the job with a few thin layers of a non-yellowing, scratch-resistant clear coat.

"I love the restoration work I do, because I can see something that's damaged and envision what it needs to be," she says. "Then all I need to do is get it there by any means possible. I tend to use a wide array of paints, tools, or techniques to replicate something. Especially on a piece that was produced anywhere within a 100-year time span. It's funny, though, because when I do my best work, it looks like I've done nothing at all."

While her day job is all about trying to perfectly recreate someone else's work, Ludwig's studio practice is where her own creative interests and ideas shine. Her mixed media pieces usually involve layers of cut paper arranged inside shadow boxes, with fragile patterns formed by thread strung between pins.

A recent wall-mounted work, "I'll Build a Coffin and Send You My Dead," is a box shaped like an upright casket, with tiers of cut maps stacked inside on the left. The collage looks like you're viewing crashing waves from above, with the undulating lines of the paper set starkly against a dark background. Both that wave-like edge and the inner right wall of the box are lined with pins, and Ludwig has intricately laced dark thread back and forth over the void.

She says she made the work "in an effort to physically lay emotions to rest," and that the cutting and layering of maps is meant to allude to chaos.

"It's so easy to put up blinders and just run through our days," Ludwig says. "I believe that there's a lot of people out there that forget just how sensitive we are, as a way to fit in to social norms. I want to point out the magic of the mundane and make people stop and think."

Ludwig says her work is the result of absorbing and piecing together inspiration from various sources, whether it's the lyrics of a song, the phenomenon of catching every green light on the way to work, or a random documentary she's found in the crevasses of the internet.

"I find it fascinating that we're constantly soaking up information whether we want to realize it or not," she says. "We sense our surroundings by touch, smell, or visceral feeling. We see and perceive, always trying to make associations and compare what's happening in the moment, based on every single other moment we've experienced in our lives. I guess the work that I make touches on that."

The 26-year-old graduated from Rochester Institute of Technology in 2014 with a Fine Arts Studio BFA. She says she's always known she wanted to be an artist, and would eagerly transform any mundane objects she could get her hands on. "Making and creating was the only thing that felt natural to me, especially if it was with uncommon materials like plastic forks or twisty ties," she says.

And while many youngsters are told to pursue a career path that's more practical than art, she had early encouragement to focus on her creativity. "I remember finger-painting in kindergarten listening to our art teacher explain that you can have a career as an artist, and it completely blew my mind," she says. "I vividly remember spinning around and saying that I thought a job was something you had to hate and that I was going to be an artist."

Ludwig doesn't speak of specifics regarding future goals, but says she plans to "keep taking risks and doing cool stuff."

"It's worked out so far," she says.

See Ludwig's work in the show, "Into the Out Of," with fellow artist Cecily Culver at The Yards Collaborative Art Space through November 10.

Alexandria Mockbee: Experimental experiences | alexandriamockbee.com

Alexandria Mockbee's art has recently shifted in a radically new direction, from drawings and paintings to experimenting with abstract paintings on film and light projection installations.

When she participated in the artist's residency at The Yards collective art space in 2016, she was creating ink and watercolor works on paper that incorporated architectural elements and viscera. Each small work presented a floating world made of bricks and geometric structures with guts and waves of sludgy fluid flowing around and through the forms.

She says that work was inspired by her observations of the physical world and inward, emotional responses. The change in her artistic process was sparked when she included a film projection installation as part of a 2017 show she had at Makers Gallery with printmaker Heather Swenson. Shot on Super 8mm film and projected onto the gallery wall, the work is what Mockbee calls a "handmade film loop with optical sound."

As the frames fly through the projector, what is projected on the wall is daubs and streaks of dark paint interrupting an otherwise empty field of bright, warm light. A slightly echoed, gravelly sound drones away during the 25-second light and shadow show. The noise nags for a number of reasons: it almost-but-not-quite matches up with the visuals, and by turns it's slightly reminiscent of the sound of a heavy piece of metal being dragged across a surface, a sustained rumble of thunder, and a distant roar.

There's no narrative and the work is entirely abstract, but it's engaging in a teasing way. Our brains want to solve puzzles. As you watch and listen to the looping film, your mind may do little flips trying to grasp and make sense of the recognizable sights and sounds. The fact that the imagery and sound match up differently each time the film loops frustrates the brain's efforts, as the brief experience is fresh each time. And viewers will experience it differently, bringing their own interpretations or emotional responses to the table.

Mockbee's new ideas began to coalesce when she decided to return to The School at Brockport and finish her undergraduate degree, and was able to take a 16mm film class at Visual Studies Workshop last semester. In that course, she learned about handmade methods, including painting on film. "That really interested me," she says, "because I was able to watch the things I was making move."

The 22-year-old is from Greece, New York, and was introduced to the arts early, having grown up playing the cello since third grade. She began exploring visual art in middle school, and went to Brockport right out of high school to earn a studio art degree, with a focus on oil painting. After a couple of years, she stopped attending and pursued an independent studio practice.

Mockbee currently works as a barista and curates the art shows at Ugly Duck café. "And I'm back in school," she says. She plans to graduate from Brockport in the spring with an undergraduate degree in Childhood Education.

The program itself is interdisciplinary, she says, and includes introductory classes in music, dance, theater, literature, and visual art. "Then you learn how to apply those and integrate that into an educational setting," she says.

It's not just about teaching dance or music to children, but "how do you use the arts to teach," she says, adding that exposing young children to the arts helps them with creative problem solving and with expressing themselves. "But also it's about integrating art into everyday life. It's a way of learning, of understanding and seeing the world."

Mockbee says she's learning professional skills in the program that could lead to a career in teaching or as an arts integration specialist, but the program's teachings also tie into her own mode of working and experiencing, and inform how she makes art now.

"The reason I moved away from a studio practice to where I am now is, I was just making two-dimensional pieces that were too stagnant for me," she says. "They weren't communicating what I was feeling, especially because I was working with abstraction, where nothing's being represented specifically. And I just found that it was not enough."

Her solution has been to move away from stationary visual art to "things that move," she says, with an emphasis on the abstract "textures" of light and sound waves. "Film is seductive," she says.

Mockbee is currently creating work that blends her own shot footage with handmade techniques. Her process is experimental and intuitive. "I'm more interested in the process and the making than the final thing that happens," she says.

Her aim isn't to produce art objects so much as it is to learn how to create temporary art experiences that are performative in nature.

"I'm interested in expanded cinema, which is, instead of just sitting and watching a film, it's like: 'How does it interact with the environment?'" she says.

Inspired by some of the dance performances she's seen from Brockport's dance department, Mockbee says she's made plans to collaborate with dancers for some of her developing work. With this addition, her work will delve further into the realm of movement-based, ephemeral performances that can never be repeated exactly the same way.