[

{

"name": "500x250 Ad",

"insertPoint": "5",

"component": "15667920",

"parentWrapperClass": "",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

The US solar industry has been on a growth streak the past few years. Between 2010 and the first half of 2017, the number of solar jobs doubled, the cost of solar installations dropped by 70 percent, and the technology went from producing a tenth of 1 percent of the country's power to 1.4 percent of it.

But President Donald Trump delivered a gut punch to the industry in January, when he signed an order establishing an aggressive tariff on imported solar cells and solar assemblies. It'll start at 30 percent this year, but will decrease each year until its 2022 expiration.

In his remarks in the Oval Office, Trump said that the tariff will create jobs, since "we'll be making solar products now much more so in the United States."

"Our companies have been decimated," he said, "and those companies are going to be coming back strong."

But the US solar industry isn't really centered on solar-cell and solar-assembly manufacturing; workers in that area account for less than 1 percent of the industry's domestic jobs. Many installers rely on imported solar panels not just because of price, but also because US makers can't meet the overall demand for panels. Trump may think the tariff could alter that dynamic, but many in the solar industry expect that would happen at the expense of installers and the manufacturers of domestic solar-energy system components.

Industry associations expect the tariffs to drive up the cost of imported solar assemblies by 10 percent. That could be enough to turn some buyers off, especially those with large projects.

"I don't think the industry expects to overcome that 30 percent tariff and sell as much solar," says Anne Reynolds, executive director of Alliance for Clean Energy New York. "They're not going to overcome it in that way. But I think they're hoping to last through a slowdown in sales."

The tariff isn't the only factor shaping the environment for solar, and for renewables as a whole. There's also a web of policies and issues playing out at the federal, state, and local levels that are influencing renewables' future.

New York and some other Northeast and Mid-Atlantic states formed the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative over a decade ago to drive down carbon emissions from power plants. The cap and trade program basically puts a price on carbon and makes low- or zero-emissions power, such as renewables, more competitive in the states' energy markets.

The recent federal tax overhaul preserved key tax credits for renewables. Many states also have policies – including tax incentives – and goals meant to increase renewable energy production. For example, New York has established a renewable energy standard that requires utilities to get half of their electricity from renewables by 2030.

"That's certainly good for renewables and good for the country at large," says Zack Dufresne, communications director for the Alliance for Clean Energy New York. "If New York can show that this works, and that spreads, that's a beautiful thing."

And still other factors will continue affecting renewables growth, including the attitudes of individual communities toward big wind turbines and utility-scale solar farms, and the intricacies of pricing solar- and wind-produced electricity.

The Trump administration's solar tariff is an urgent threat, a big action that's likely to have an immediate and harmful effect on the nation's growing solar industry. And for that reason, it's getting a lot of attention right now.

The tariff came out of a trade case brought by Suniva, a US-based solar panel maker whose majority owner is a Chinese investment firm. SunWorld, whose German parent company went bankrupt, joined the case later. Both companies argued that foreign solar cells and solar assemblies were hurting their business, and they sought protections far more severe than the tariff Trump approved.

The trade case "unfortunately came at a time where the federal administration was more interested in making a statement about imports than avoiding something that would actually cost jobs," says Reynolds.

Roughly 260,000 people work in the US solar industry and around 2,000 of them are tied to the manufacture of solar cells and panels. Another 36,000 make things such as the racks that solar panels go on or electrical components used in solar arrays. Most work in sales, design, or installation, as well as financial or legal support positions.

The Solar Energy Industry Association says as many as 23,000 people, from factory workers to installers, could lose their jobs this year because of the tariff.

If fewer customers buy the panels because of increased cost, "it will be telegraphed through the rest of the system, so domestic installers and domestic component manufacturers will also face some level of reduced business," says Karl Rabago, executive director of Pace University law school's Energy and Climate Center. "That, by the way, is where the layoffs will happen in the United States."

But the tariff's effect won't be felt evenly across the industry.

Bob Kanauer of LTHS Solar in Penfield says he doesn't expect the tariff to impact his business much, since his customers "pretty much demand" US-made equipment. And he expects that even with the tariff, some of the foreign-made panels will still be cheaper.

The tariff will mostly impact large projects and buyers who are looking for the absolute lowest price possible on a solar energy system, he says.

SunCommon, a 60-employee company based in the Town of Ontario, designs and builds residential, commercial, and community solar projects. Kevin Schulte, the company's CEO, says the tariff is having a minimal impact on the quotes SunCommon is currently getting from its suppliers. And the systems are still cheaper than buying electricity from a utility, he says.

Schulte says he's more concerned about the challenges posed by the artificially low price of natural gas and the persistent misbelief that Upstate New York doesn't get enough sun for solar to work. Some parts of the year are more productive than others, but about the only time panels don't produce electricity during the daylight hours is when they are blocked by snow.

Solar is attractive to many people and businesses because it's a clean energy source that lessens their contribution to climate change. But its economics make it feasible. Buyers are recouping their investment through energy savings faster than they used, to thanks to rapid, drastic improvements in the technology and a sharp drop in systems' prices. As a result, the number of solar installations has soared. In 2017, New York had 78,323 solar systems – from individual home systems to utility solar farms. That number was 9,079 in 2011.

The tariff threatens to upset the economic dynamics working in solar's favor. And just as it is affecting different parts of the solar industry differently, it may hit some places in the US harder than others.

"New York's probably fine from the tariff," Schulte says. It'll most impact project development in markets where solar is already lagging, he says.

Pace Energy and Climate Center's Rabago echoes what Schulte says about New York. The state has a good solar resource and strong policies that support the technology, they say. Some of the policies are very technical, but others aren't, such as tax incentives for buyers. And the state's renewable-energy standard should also accelerate renewables growth, they say.

Massachusetts also has strong solar policies and good resources, Schulte and Rabago say. California and Arizona, which both have far more large, utility-scale solar farms than New York, may take a hit. But the already strong solar industries in those states should prove resilient.

The Carolinas and Georgia may be in a more precarious position when it comes to solar, Schulte says. Both have low electricity prices and don't have policies as aggressive as New York's, he says.

And Rabago says that foreign solar producers will likely find a way to bring down the cost of the panels to compensate for the tariff to some extent, Rabago says. Since solar energy systems have already been getting cheaper, it's possible that the tariff could just slow that trend or that prices could flatten, he says.

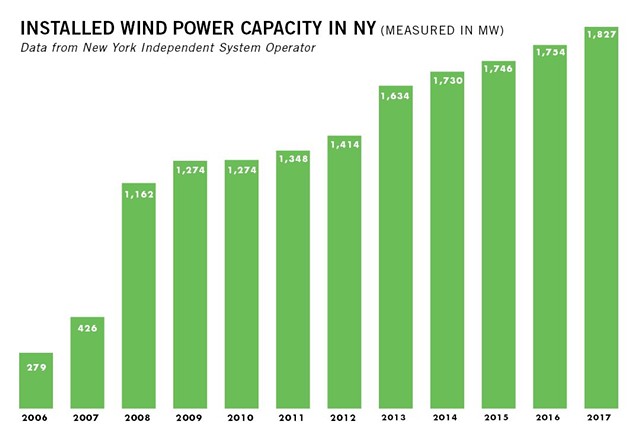

Just as New York's renewable energy standard is meant to encourage accelerated growth in solar, it's also meant to encourage new-wind energy projects. But wind farm developers are facing problems that the standard on its own does not address.

Large wind energy projects have to complete a complex siting process – the same process any new power plan in new York goes through – that lasts years. The Cassadaga Wind Project – which includes up to 48 turbines in a few Chautauqua County towns – received approval after a three-year review.

That process is led by a siting board that operates out of the state Department of Public service, which regulates New York utilities. That board weighs local concerns and is supposed to take into account local laws, though its members can override overly-burdensome local laws.

Public polls show substantial support for wind power in New York, but that doesn't square with the reception some projects have been getting.

"What we're running into more and more is local opposition, which is becoming more organized, seems to be very well-funded," Dufresne says.

That very conflict is playing out in Yates, Orleans County, and its Niagara County neighbor, Somerset. Apex Clean Energy has proposed a large wind project spread over 12 miles in the two towns, and while some community members want the project, a very vocal group opposes it, as do elected leaders in both towns.

The arguments for and against the project are pretty familiar at this point: those in favor point to the clean energy potential as well as the revenue for landowners and local governments. Those who oppose it cite concerns about safety, noise, blade shadows, environmental damage, and the sight of tall turbines.

Somerset, and recently Yates, have enacted local laws that don't outright ban the turbines, but effectively prohibit them through severe restrictions such as setbacks.

But that doesn't change the fact that the state needs big renewable projects – including wind turbines – to meet its goal, Dufresne says. And the state needs to make progress on moving larger projects forward, he says. The siting board is reviewing several wind and solar farm applications.

"Our developers tend to be pretty flexible in developing these projects and really, really want to work with the community," Dufresne says. "They're desperate to work with the community in some circumstances, to get this right and to provide the benefits that the community's then going to enjoy."

Despite the obstacles, renewables supporters are optimistic about wind energy's potential. And while some Upstate projects struggle, the state is actively encouraging offshore wind development to provide large amounts of clean energy to New York City and Long Island.

Governor Andrew Cuomo says he wants 2,400 megawatts of offshore wind-power generation built off of New York's Atlantic coast by 2030. And to help get there, state agencies and the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority completed a detailed master plan identifying sites for offshore wind turbine development and laying out how to get that power to New York customers.

Deepwater Wind is already moving forward on an offshore wind project near Long Island. It's leased 256 square miles of the ocean floor from the federal government, and the Long Island Power Authority has approved the project, according to a New York Times report from January 2017.

NYSERDA will also solicit proposals this year and next for at least 800 megawatts of offshore wind power; that's enough energy to power 400,000 households. By committing to buy that power, the agency will help guarantee the viability of one or more offshore wind projects.

New York is seeing some other encouraging developments on the renewables front, the bulk of them also driven by the state's clean energy standard. Clean energy advocates say the state also has some simple yet untapped opportunities to make the state more renewables-friendly.

They say the state should ramp up efforts to make homes, factories, and commercial buildings more energy efficient. After all, the cleanest and cheapest power is that which doesn't have to be generated in the first place.

"In New York, we have had a lot of good talk about energy efficiency but we're a little behind – a lot behind – where we should be," Rabago says.

The state has invested in making some farms and commercial buildings more energy efficient. It's set up a fund to help support those types of efficiency efforts. But Cuomo wants the state to get more aggressive about energy efficiency, so in January he directed the state Public Service Commission and NYSERDA to develop an energy efficiency standard. And he gave them a deadline of Earth Day, April 22. The state would help fund projects and initiatives aimed at meeting the goal, but utilities would also have to make efforts of their own.

Cuomo is also pledging $200 million in state funding to help add energy storage capacity to the state's grid. Why is that important? Solar and wind power are intermittent, so the times the generators are producing power don't always match up with the times people need it. Energy storage – giant, utility-scale batteries, more or less – allows excess electricity to be stored away until it's needed.

New Yorkers are also showing more and more interest in renewables projects, particularly solar arrays, that are intended to provide low-cost power to specific neighborhoods or communities. Many people and businesses can't install solar energy systems, either because they can't afford to, their properties aren't suited for an array, or because they rent. Community-scale solar energy systems, which are larger than single-home systems but nowhere near the size of utility-scale solar farms, provide a way for practically anyone to buy solar-generated electricity, and generally with some costs savings.

And SunCommon's Schulte says there's a general trend toward displacing fossil fuel-powered technologies with electrified ones; electric vehicles displacing gasoline-powered vehicles, for example. Battery storage will become cost competitive and technologies such as heat pumps, which are a type of heating and cooling system, will become more widely used. As that shift happens, making sure the new technologies are powered by clean energy will be very important.

On-site renewables, energy storage, and electrified technology can even make individual homes more self-sufficient, at least for their own power needs. Schulte says we're looking at a future where charged car batteries could power a house if the electricity goes out, for example

"You create this resiliency that's really a phenomenal thing to think about," Schulte says.

In Monroe County, this sort of shift is starting to happen. It currently has 854 completed projects: 759 are residential, 83 are classified as small commercial, and 12 are classified as commercial or industrial. (Think of the large array that Bausch + Lomb built next to its North Goodman Street factory.)

And there's clear interest from more customers. Another 104 solar installations are in the works; statewide there are 5,125 pending solar projects. Schulte says his company's December and January solar energy systems sales were double what they were last year, and that happened despite a harsh winter where people may not be thinking about the sun and solar.

"It's just a piece of glass that sits on your rooftop and generates electricity," Schulte says. "What could be bad?"