"The History of Space Photography""Astro-Visions"

Everlasting frontier

By Rebecca Rafferty @rsrafferty[

{

"name": "500x250 Ad",

"insertPoint": "5",

"component": "15667920",

"parentWrapperClass": "",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

"Yearning" is a good word, to sum it up. Since we gained consciousness, humans have gazed with wonder out into the fathomless depths of the sky, in search of some unknowable creator, to begin to understand the complex laws that govern this existence — and ultimately to better understand ourselves and our place in this fever dance of creation and destruction. The two current space-themed shows at George Eastman House reflect this search, capturing the everlasting marvel of staring up and out, retracing the history of our documentary tool-making and -refining, and revealing how humanity defiantly stretches the boundaries of what we can know.

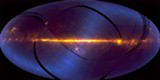

Visitors to the museum's Brackett Clark Gallery first encounter "Sky Survey," a massive, pixilated image that is an infrared representation of the whole universe, from our perspective, which only hints at the vastness surrounding us. Viewing the image comes with the stark realization that this image — save for minor improvements in technology over time — is the closest we will ever get to viewing the universe in its entirety.

This single image, humbling in its vastness of scope as well as its proof of our limitations, sets the tone for the rest of the exhibit, which retraces mankind's path of space (and Earth) exploration, and reframes our perceptions of the photograph as a representative of data collected over time and across spectra we cannot detect with our own dim senses.

Curated by Jay Belloli, and organized by the California/International Arts Foundation in Los Angeles, the first portion of this double space show is "The History of Space Photography," which explores the variety of astronomical photographs that have been created since we developed the technology to "draw with light." These images range from the watery, flat, first-known image of the moon, taken in 1840 by John W. Draper, to images of the cold and dusty Mars landscape currently being snapped and sent back to us by the Curiosity rover.

Wonderful images and supplemental videos provide information about the limitless intrigue found in our own solar system. An early image of Mars depicts a blur that was thought to be a problem with the film, but was in fact a surprise cloud in our neighboring planet's atmosphere. Definitions over time grow shifty, as distant planets seem more moon-like and distant moons reveal more planetoid traits. As our knowledge expands, our understanding of the possibility of extraterrestrial life tiptoes beyond the bounds of the conditions for life as we know it.

The first entire, un-shadowed image of our marbled Earth, captured in a single shot in 1972, still evokes the same breathtaking awe as when it was first spied, which can only ever be a fragment of what was felt by those aboard that space shuttle, staring back at the entirety of their suspended, distant home. An inky shot of the globe with bright clusters of city lights reveals, at once, the majority of us doing what we do: holding the darkness at bay. John Glenn's 1962 snapshot of Earth's eggshell atmosphere is fragile and improbable and radiant in the void.

Leaving the first room of early photography and our local star system, the second room explores deeper space, as well as how we have turned the cameras back on ourselves for the most critical of gazes.

Images of galaxies, pulsars, quasars, and the formation and dissolution of stars dazzle. Four views of the North American Nebula, which from our perspective is located among the stars that make up the constellation we call Cygnus, reveal energy radiating from the exact same area of the sky, in different parts of the spectrum, cluing us in to things that are found there both visible and invisible to the naked human eye. Enhanced images strive to illustrate dark matter and dark energy — concepts that are difficult to talk about effectively, much less depict.

As for our planet, scores of images shot from far above detail changes in vegetation and resources, oceanography, geology, and climate over time periods both short and long. One particularly sobering section of the exhibit reveals rampant deforestation of the Amazon, the trailing ribbons of oil leaked in the Gulf Coast, and a disturbing image enhanced to reveal radiation levels in the Pacific before and after the 2011 level 9.0 earthquake and Fukushima nuclear reactor disaster. I don't understand the terminology well enough to properly discern the meaning behind these maps, but there is a vast and startling difference between those two images.

The museum is simultaneously showing "Astro-Visions," a series of images from the museum's collection, curated by Jamie M. Allen, assistant curator of photographs at George Eastman House. "Astro-Visions" is a playful exploration of space and the human imagination, ranging from early imaginative views of the lunar landscape — really models of peaks and craters that were created and photographed by James Hall Nasmyth and James Carpenter in the 1870's — to stills from highly inspired sci-fi films and TV shows throughout the decades, to Seattle-based artist Bill Finger's "Ground Control" series of photographs of hand-built dioramas and miniatures, which explore the aching desire of the imaginative everyman who is offered a shot at space.

In one of Finger's five large photos, a spacesuit-clad person climbs a ladder to enter an attic, as if emerging from a shuttle into space. In another, a playground contains a rocket slide. In still another shot, a detailed shuttle constructed of wood planks and pipes has the feeling of a very serious backyard playhouse.

William Larson's mysterious image, "Untitled," theatrically juxtaposes the serenity of a young girl caught swinging in front of the swollen moon with a still of an imploding building. The work is overlaid with stage directions that seem to subtly comment on the indifference of the violent universe on both micro and macro levels, and the unreachable escape. Curiously, Gil Scott-Heron's voice reverberates in my head: "and Whitey's on the moon."

Speaking of...

Latest in Art

More by Rebecca Rafferty

-

Beyond folklore

Apr 4, 2024 -

Partnership perks: Public Provisions @ Flour City Bread

Feb 24, 2024 -

Raison d’Art

Feb 19, 2024 - More »