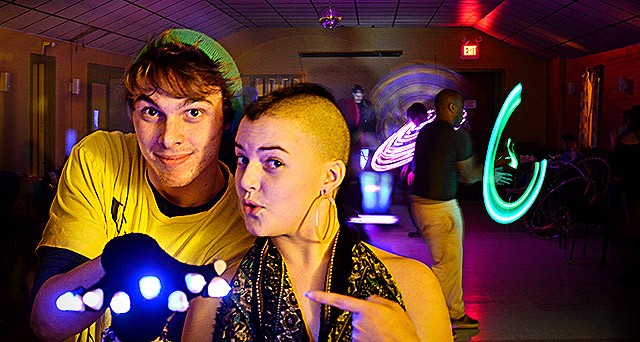

Rich Riggs and Taima Probst at the Flying Squirrel's Whirly Wednesday dance and music night.

[

{

"name": "500x250 Ad",

"insertPoint": "5",

"component": "15667920",

"parentWrapperClass": "",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

Zachary Ceru placed his toy hoop over his head and stepped out on the dance floor. The brightly-colored ring glowed in the dark as it swung from Ceru's neck with hooping's familiar twirl. After a minute or two, Ceru let the hoop drop over his torso to his waist, where it rolled around his hips and abdomen with ease.

Ceru was one of about 40 hoopers at a recent Whirly Wednesday, one of the Flying Squirrel Community Space's most popular weekly events. By 9 p.m. most Wednesdays, the Squirrel's second floor holds a hoard of mostly young hoopers, gyrating in the dark to thumping dance mixes.

"I've been doing this for about nine months," Ceru says. "It's sort of like dancing, but it's different."

The Flying Squirrel Community Space at 285 Clarissa Street is home to a potpourri of progressive artists, musicians, and social justice activists. If visitors weren't interested in the carnival whimsy of Whirly Wednesday, for example, they could've joined a Take Back the Land meeting under way simultaneously on the Squirrel's first floor.

That night, about 20 Take Back the Land activists discussed how they could help a woman reacquire her northeast-area home of 30 years. The home had been foreclosed upon.

The Squirrel is partly a meeting space. But it's also an organization with its own members, who tend to describe it as a collective: a community that's part of other communities.

There's a gritty sense of multiplicity about the Squirrel that's immediately evident once you're inside the front door. The foyer is feathered with pamphlets and flyers about meetings on everything from reproductive rights to anarchy. And most of the building's rooms serve multiple purposes: a meeting room can be transformed into a dining hall and a dance floor can be converted to a classroom.

Rochester Indymedia, the Green Party, and Worker Justice — an activist group for low-wage workers — are some of the groups that meet at the Squirrel. But the groups change and new groups form. Last month, some members began forming the Free School, an information exchange with classes like building a solar oven and permaculture.

The Squirrel also hosts a robust music lineup of local bands. Community dinners and neighborhood socials are popular events, too.

In some respects, the Squirrel's roots can be traced to the European salons of the 17th and 18th centuries, which were sanctuaries for art, philosophy, literature, and political discourse. In other ways, the Squirrel is reminiscent of the collectives of the 1960's, where hippies and the counter culture were galvanized by a central belief; often it was a return to an agrarian lifestyle, simplicity, and a rejection of consumerism.

Some of those concerns bare an uncanny resemblance to the Squirrel's "Principles of Unity," the doctrine that binds members to the collective. It says community is the pathway to freedom, and that racism, sexism, heterosexism, and especially capitalism, are opposed. Conflicts are resolved, as much as possible, through alternative justice solutions that don't rely on police intervention.

The Squirrel began a few years ago with about nine founding members, says co-founder Dawn Zuppelli. Many of the founders knew each other from the now closed Storefront Antiwar Crisis Center, formerly at 658 Monroe Avenue.

The principles are the members' core values, Zuppelli says, and came about after a lot of discussion.

"They aren't set in stone," she says. "The Squirrel is an evolving organization. It depends on who joins the collective."

Membership in the Squirrel is easy, but far from simplistic: come to the meetings and participate. Know the principles and understand that members live by them. There are no membership dues or complicated application forms, but members generally agree to volunteer some of their time each month toward some type of administrative or building maintenance need.

What is less fluid, Zuppelli says, is how the Squirrel operates.

"It is so horizontally structured," she says. "All members are created equal."

Members only speak about the Squirrel from their own perspective, but no one speaks on behalf of the Squirrel or its members, Zuppelli says. And no one member makes decisions on behalf of everyone, she says. All decisions are made through reaching a consensus.

"It can be more time-consuming, but it's also more fun and creative," she says. "We don't often get to experience this in the outside world."

Ted Forsyth, another Squirrel co-founder, says methodology is important to the members.

"We trade-in expediency and efficiency for a sort of patience and accountability," he says. "We don't expect any one person to be a leader. We're all leaders."

Before purchasing the building on Clarissa Street, Forsyth says there were a lot of activist groups meeting in Rochester on issues ranging from education to homelessness. Meetings were held everywhere from cafes to shelters.

The groups at the Squirrel are autonomous, he says, and their members aren't necessarily members of the Squirrel. But the Squirrel serves more as a clearinghouse, Forsyth says, and what makes it dynamic is the opportunity to co-mingle, share ideas, and sometimes work with other activists and artists.

"I wouldn't call it [the Squirrel] a movement," Forsyth says. "But it's sort of facilitating movements."

The Squirrel's location is significant, too, says longtime member Ricardo Adams, because of Clarissa Street's rich history as one of the main business and cultural arteries of Rochester's African-American community.

"This was a 99 percent, maybe 100 percent black community," he says. "And it was a vibrant community. We had everything from corner grocery stores and clothing stores to barbershops and entertainment. You didn't really even have to leave Clarissa Street. It all happened right here."

Even the Squirrel's building is historically significant, Adams says. In 1906, the Elks Lodge No. 91 Flower City Chapter and the Eldorado Temple No. 32 Auxiliary used the site for their meetings. The mostly African-American membership met there after being rejected by the Benevolent Protective Order of the Elks of the World, a largely white organization at the time.

When the Squirrel's founding members purchased the rundown and abandoned building for roughly $35,000, they decided to leave the old Elks bar as a reminder of their work, Adams says. And some of the Elks' meeting minutes and notes have been archived, he says.

"They really did a lot for this community," he says. "They provided scholarships and they supported the people in a lot of different ways."

Clarissa Street's musical legacy is also well-documented. During the mid-20th century, jazz artists from all over the country played at the Pythodd Club, and what is now Clarissa's night club. The latter is located next door to the Squirrel.

These days, Adams and his wife, Rochester school board member Mary Adams, have resumed some of the Elks' neighborhood work. They coordinate a community dinner at the Squirrel on the last Saturday evening of the month.

"We've served as many as 70 people here," Richardo Adams says. "And we do it without help from Wegmans or Foodlink or any of the big organizations. This is just people helping people."

Last month, Mary Adams made fish fry plates for about 30 people. Other volunteers brought Greek salad, rice and beans, and brownies for dessert.

"By the last Saturday of the month, food gets low for a lot of families," she says. "I do this because I believe building our community is the answer to most of our problems."

And the Squirrel is contributing to Clarissa Street's musical legacy, too, says longtime Squirrel member Al Brundage.

"When they [Squirrel members] said we need to have a manager on site if we're going to be a music venue, I said, 'I'll do it,' without giving it a second thought and I love it," he says.

Brundage says the Squirrel is an important music venue in Rochester, especially for younger musicians and band members. The Squirrel doesn't serve or allow alcohol on the premises, which makes it easier for a band of underage musicians to play there. The policy also makes it easier for younger fans to come hear the bands.

Most of the bands play some type of punk, and one band in particular, The Setbacks, got its start playing at the Squirrel, Brundage says.

"Now they're playing Buffalo and Syracuse, and all over the place," he says.

But the Squirrel has had to clear some hurdles, too. In the Squirrel's early days, there were a few complaints from neighbors about the noise from the bands. But the Squirrel's members have addressed those concerns, Brundage says.

Amplified music ends at 10 p.m. and acoustic may go to 11 p.m., he says.

Long-term funding was another issue that needed to be addressed. While the Squirrel accepts donations, it doesn't apply for grants like most nonprofits. The members don't want to become part of what they call the "nonprofit industrial complex."

Grants create a false sense of security, some members say, and often come with strings attached that dictate not only how the money can be spent, but how the Squirrel needs to operate to be eligible.

So members came up with a promotion, "25@25: Keeping the Squirrel Alive." Participants pay $25 a month for a year in exchange for the ability to hold two free events at the Squirrel, such as a birthday or graduation party. The money is just enough to handle repairs and emergencies," members say.

One of the Squirrel's most difficult tests came when members decided that a particular activist group could no longer hold its meetings there. Individual members of that group are still welcome at the Squirrel, but the group's tactics and philosophy began to conflict with the Squirrel's principles of unity, says co-founder Dawn Zuppelli.

The decision was an emotionally charged one, she says, because the Squirrel was founded on inclusiveness and engagement.

"It's not an exclusive club," she says.

One of the Squirrel's more interesting challenges has been outreach to the Corn Hill neighborhood. Squirrel members and some of the groups that use the space oppose urban gentrification, but Corn Hill was one of the city's early neighborhood gentrification successes. But the Squirrel seems to have earned the respect of its neighbors.

"When certain neighborhoods become historic and trendy, whether intentional or not, it raises the value of the property and it hurts poor people, particularly people of color," says Squirrel member Ryan Acuff. "I think you can have revitalization without gentrification."

Still, the Squirrel has gone out of its way to be part of the Clarissa Street and Corn Hill communities, he says.

"Many of us are dreamers," he says. "We're building relationships around hope."

Speaking of...

Latest in News

More by Tim Louis Macaluso

-

RCSD financial crisis builds

Sep 23, 2019 -

RCSD facing spending concerns

Sep 20, 2019 -

Education forum tomorrow night for downtown residents

Sep 17, 2019 - More »